Edition 6.1

Dana Lee Ling

Introduction to Statistics Using Google Sheets™

Dana Lee Ling

College of Micronesia-FSM

Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia

QA276

Google Sheets™ web-based spreadsheet program © 2018 Google Inc. All rights reserved. Google Sheets is a trademark of Google Incorporated. Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

Creative Commons -by 4.0

For material not reserved to other owners,

Introduction to Statistics Using Google Sheets™

by Dana Lee Ling is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Introduction to Statistics Using Google Sheets™

Table of Contents

Chapters

Google Slides presentations

Stats 01 Introduction Population Samples Levels of Measurement

Stats 02 Measures of middle and spread

Stats 03 Visualizing data

Stats 04 Paired Data and Scatter Diagrams

Stats 05 Probability

Stats 07 Introduction to the Normal Distribution

Stats 08 Sampling distribution of the mean

Stats 09 Confidence intervals

Stats 10 Hypothesis testing

Stats 11 Testing for a difference between two sample means with the t-test

Stats 12 Data exploration

Preface

We all walk in an almost invisible sea of data. I walked into a school fair and noticed a jump rope contest. The number of jumps for each jumper until they fouled out was being recorded on the wall. Numbers. With a mode, median, mean, and standard deviation. Then I noticed that faster jumpers attained higher jump counts than slower jumpers. I saw that I could begin to predict jump counts based on the starting rhythm of the jumper. I used my stopwatch to record the time and total jump count. I later find that a linear correlation does exist, and I am able to show by a t-test that the faster jumpers have statistically significantly higher jump counts. I later incorporated this data into the fall 2007 final.

I walked into a store back in 2003 and noticed that Yamasa™ soy sauce appeared to cost more than Kikkoman™ soy sauce. I recorded Yamasa and Kikkoman soy sauce prices and volumes, working out the cost per milliliter. I eventually showed that the mean price per milliliter for Yamasa was significantly higher than Kikkoman. I also ran a survey of students and determined that the college students prefer Kikkoman to Yamasa.

As a child my son liked articulated mining dump trucks. I found pictures of Terex™ dump trucks on the Internet. I wrote to Terex in Scotland and asked them about how the prices vary for the dump trucks, explaining that I teach statistics and thought that I might be able to use the data in class. "Funny you should ask," a Terex sales representative replied in writing. "The dump trucks are basically priced by a linear relationship between horsepower and price." The representative included a complete list of horsepower and price Terex articulated dump trucks.

One term I learned that a new Cascading Style Sheets level 3 color specification for hue, luminosity, and luminance had been released for HyperText Markup Language web pages. The hues were based on a color wheel with cyan at the 180° middle of the wheel. I knew that Newton had put green in the middle of the red-orange-yellow-green-blue-indigo-violet rainbow, but green is at 120° on a hue color wheel. Green is not the middle of the hue color wheel. And there is no cyan in Newton's rainbow. Could the middle of the rainbow actually be at 180° cyan, or was Newton correct to say the middle of the rainbow is at 120° green? I used a hue analysis tool to analyze the image of an actual rainbow taken by a digital camera here on Pohnpei. This allowed an analysis of the hue angle at the center of the rainbow.

While researching sakau consumption in markets here on Pohnpei I found differences in means between markets, and I found a variation with distance from Kolonia. This implied a relationship between the strength of sakau and the distance from the centrally located town of Kolonia. I asked some of the markets to share their cup tally sheets with me, and a number of the markets obliged. The sakau data suggested that sakau strength was related to the distance from Kolonia.

The point is that we are surrounded by data. You might not go into statistics professionally, yet you will always live in a world filled with data. During this course my hope is that you experience an awareness of the data around you.

Data flows all around you.

A sea of data pours past your senses daily.

A world of data and numbers. Watch for numbers to happen around you. See the matrix.

Curriculum note

The text and the curriculum are an evolving work. Some curriculum options are not specifically laid out in this text. One option is to reserve time at the end of the course to engage in open data exploration. Time can be gained to do this by de-emphasizing chapter five probability, essentially omitting chapter six, and skipping from the end of section 7.2 directly to chapter 8. This material has been retained as these choices should be up to the individual instructor.

For the first time since the inception of the online text, the sections were renumbered from edition 6.0 to 6.1. Content was not changed, but pre-existing links into the text will be broken in places. The section numbers were reworked in some places in part of a move towards support remote learners.

Statistics studies groups of people, objects, or data measurements and produces summarizing mathematical information on the groups. The groups are usually not all of the possible people, objects, or data measurements. The groups are called samples. The larger collection of people, objects or data measurements is called the population.

Statistics attempts to predict measurements for a population from measurements made on the smaller sample. For example, to determine the average weight of a student at the college, a study might select a random sample of fifty students to weigh. Then the measured average weight could be used to estimate the average weight for all student at the college. The fifty students would be the sample, all students at the college would be the population.

Population: The complete group of elements, objects, observations, or people.

Parameters: Measurements of the population: population size N, population median, population mean μ...

Sample: A part of the population. A sample is usually more than five measurements, observations, objects, or people, and smaller than the complete population.

Statistics: Measurements of a sample: sample size n, sample median, sample mean x.

Examples

We could use the ratio of females to males in a class to estimate the ratio of females to males on campus. The sample is the class. The intended population is all students on campus. Whether the statistics class is a "good" sample - representative, unbiased, randomly selected, would be a concern.

We could use the average body fat index for a randomly selected group of females between the ages of 18 and 22 on campus to determine the average body fat index for females in the FSM between the ages of 18 and 22. The sample is those females on campus that we've measured. The intended population is all females between the ages of 18 and 22 in the FSM. Again, there would be concerns about how the sample was selected.

Measurements are made of individual elements in a sample or population. The elements could be objects, animals, or people.

The sample size is the number of elements or measurements in a sample. The lower case letter n is used for sample size. If the population size is being reported, then an upper case N is used. The spreadsheet function for calculating the sample size is the COUNT function.

=COUNT(data)

If one wants to count the sample size for a nominal level list of words, the COUNTA function is used.

=COUNTA(data)

Data can be put into categories such as words or numbers, countable and uncountable, and into levels of measurement.

There are four levels of measurement. In this text most of the data and examples are at the ratio level of measurement.

The levels of measurement can also be thought of as being nested. For example, ratio level data consists of numbers. Numbers can be put in order, hence ratio level data is also orderable data and is thus also ordinal level data. To some extent, each level includes the ones below that level. The highest level of measurement that a data could be considered to be is said to be the level of measurement. There are instances where qualitative data might be placed in an order and thus be considered ordinal data, thus ordinal level data may be either qualitative or quantitative. When a survey says, "Strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree" the data technically consists of answers which are words. Yet these words have an order, in some instances the answers are mapped to numbers and a median value is then calculated. Above the ordinal level the data is quantitative, numeric data.

Note that at higher levels, such as at the ratio level, the mean is usually chosen to represent the middle, but the median and mode can also be calculated. Statistics that can be calculated at lower levels of measurement can be used in higher levels of measurement.

Descriptive statistics: Numerical or graphical representations of samples or populations. Can include numerical measures such as mode, median, mean, standard deviation. Also includes images such as graphs, charts, visual linear regressions.

Inferential statistics: Using descriptive statistics of a sample to predict the parameters or distribution of values for a population.

The number of measurements, elements, objects, or people in a sample is the sample size n. A simple random sample of n measurements from a population is one selected in a way that:

Ensuring that a sample is random is difficult. Suppose I want to study how many Pohnpeians own cars. Would people I meet/poll on main street Kolonia be a random sample? Why? Why not?

Studies often use random numbers to help randomly selects objects or subjects for a statistical study. Obtaining random numbers can be more difficult than one might at first presume.

Computers can generate pseudo-random numbers. "Pseudo" means seemingly random but not truly random. Computer generated random numbers are very close to random but are actually not necessarily random. Next we will learn to generate pseudo-random numbers using a computer. This section will also serve as an introduction to functions in spreadsheets.

Coins and dice can be used to generate random numbers.

This course presumes prior contact with a course such as CA 100 Computer Literacy where a basic introduction to spreadsheets is made.

The random function RAND generates numbers between 0 and 0.9999...

=rand()

The random number function consists of a function name, RAND, followed by parentheses. For the random function nothing goes between the parentheses, not even a space.

To get other numbers the random function can be multiplied by coefficient. To get whole numbers the integer function INT can be used to discard the decimal portion.

=INT(argument)

The integer function takes an "argument." The argument is a computer term for an input to the function. Inputs could include a number, a function, a cell address or a range of cell addresses. The following function when typed into a spreadsheet that mimic the flipping of a coin. A 1 will be a head, a 0 will be a tail.

=INT(RAND()*2)

The spreadsheet can be made to display the word "head" or "tail" using the following code:

=CHOOSE(INT(RAND()*2),"head","tail")

A single die can also be simulated using the following function

=INT(6*RAND()+1)

To randomly select among a set of student names, the following model can be built upon.

=CHOOSE(INT(RAND()*5+1),"Jan","Jen","Jin","Jon","Jun")

To generate another random choice, press the F9 key on the keyboard. F9 forces a spreadsheet to recalculate all formulas.

When practical, feasible, and worth both the cost and effort, measurements are done on the whole population. In many instances the population cannot be measured. Sampling refers to the ways in which random subgroups of a population can be selected. Some of the ways are listed below.

Census: Measurements done on the whole population.

Sample: Measurements of a representative random sample of the population.

Today this often refers to constructing a model of a system using mathematical equations and then using computers to run the model, gathering statistics as the model runs.

To ensure a balanced sample: Suppose I want to do a study of the average body fat of young people in the FSM using students in the statistics course. The FSM population is roughly half Chuukese, but in the statistics course only 12% of the students list Chuuk as their home state. Pohnpei is 35% of the national population, but the statistics course is more than half Pohnpeian at 65%. If I choose as my sample students in the statistics course, then I am likely to wind up with Pohnpeians being over represented relative to the actual national proportion of Pohnpeians.

| State | 2010 Population | Fractional share of national population (relative frequency) | Statistics students by state of origin spring 2011 | Fractional share of statistics seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuuk | 48651 | 0.47 | 10 | 0.12 |

| Kosrae | 6616 | 0.06 | 7 | 0.09 |

| Pohnpei | 35981 | 0.35 | 53 | 0.65 |

| Yap | 11376 | 0.11 | 12 | 0.15 |

| 102624 | 1.00 | 82 | 1.00 |

The solution is to use stratified sampling. I ensure that my sample subgroups reflect the national proportions. Given that the sample size is small, I could choose to survey all ten Chuukese students, seven Pohnpeian students, two Yapese students, and one Kosraean student. There would still be statistical issues of the small subsample sizes from each state, but the ratios would be closer to that seen in the national population. Each state would be considered a single strata.

Used where a population is in some sequential order. A start point must be randomly chosen. Useful in a measuring a timed event. Never used if there is a cyclic or repetitive nature to a system: If the sample rate is roughly equal to the cycle rate, then the results are not going to be randomly distributed measurements. For example, suppose one is studying whether the sidewalks on campus are crowded. If one measures during the time between class periods when students are moving to their next class - then one would conclude the sidewalks are crowded. If one measured only when classes were in session, then one would conclude that there is no sidewalk crowding problem. This type of problem in measurement occurs whenever a system behaves in a regular, cyclical manner. The solution would be ensure that the time interval between measurements is random.

The population is divided into naturally occurring subunits and then subunits are randomly selected for measurement. In this method it is important that subunits (subgroups) are fairly interchangeable. Suppose we want to poll the people in Kitti's opinion on whether they would pay for water if water was guaranteed to be clean and available 24 hours a day. We could cluster by breaking up the population by kousapw and then randomly choose a few kousapw and poll everyone in these kousapw. The results could probably be generalized to all Kitti.

Results or data that are easily obtained is used. Highly unreliable as a method of getting a random samples. Examples would include a survey of one's friends and family as a sample population. Or the surveys that some newspapers and news programs produce where a reporter surveys people shopping in a store.

In science, statistics are gathered by running an experiment and then repeating the experiment. The sample is the experiments that are conducted. The population is the theoretically abstract concept of all possible runs of the experiment for all time.

The method behind experimentation is called the scientific method. In the scientific method, one forms a hypothesis, makes a prediction, formulates an experiment, and runs the experiment.

Some experiments involve new treatments, these require the use of a control group and an experimental group, with the groups being chosen randomly and the experiment run double blind. Double blind means that neither the experimenter nor the subjects know which treatment is the experimental treatment and which is the control treatment. A third party keeps track of which is which usually using number codes. Then the results are tested for a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Placebo effect: just believing you will improve can cause improvement in a medical condition.

Replication is also important in the world of science. If an experiment cannot be repeated and produce the same results, then the theory under test is rejected.

Some of the steps in an experiment are listed below:

Observational studies gather statistics by observing a system in operation, or by observing people, animals, or plants. Data is recorded by the observer. Someone sitting and counting the number of birds that land or take-off from a bird nesting islet on the reef is performing an observational study.

Surveys are usually done by giving a questionnaire to a random sample. Voluntary responses tend to be negative. As a result, there may be a bias towards negative findings. Hidden bias/unfair questions: Are you the only crazy person in your family?

The process of extending from sample results to population. If a sample is a good random sample, representative of the population, then some sample statistics can be used to estimate population parameters. Sample means and proportions can often be used as point estimates of a population parameter.

Although the mode and median, covered in chapter three, do not always well predict the population mode and median, there are situations in which a mode may be used. If a good, random, and representative sample of students finds that the color blue is the favorite color for the sample, then blue is a best first estimate of the favorite color of the population of students or any future student sample.

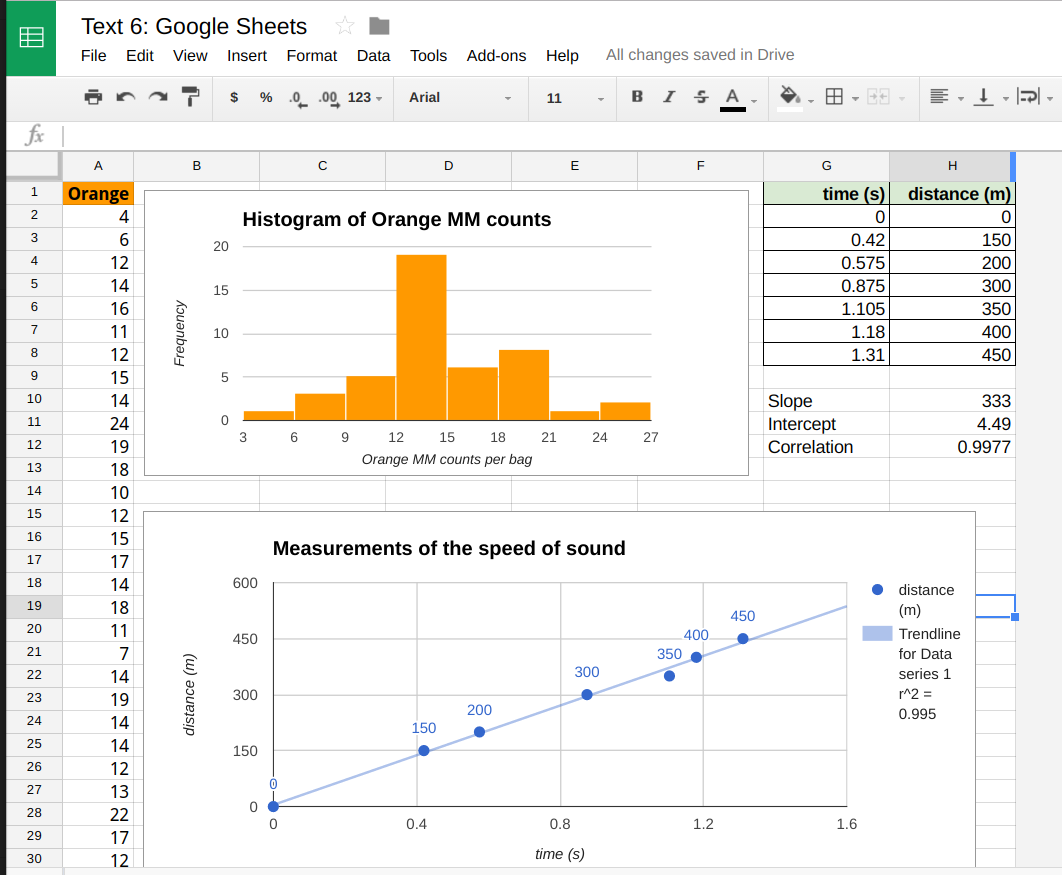

| Favorite color | Frequency f | Relative Frequency or p(color) |

|---|---|---|

| Blue | 32 | 35% |

| Black | 18 | 20% |

| White | 10 | 11% |

| Green | 9 | 10% |

| Red | 6 | 7% |

| Pink | 5 | 5% |

| Brown | 4 | 4% |

| Gray | 3 | 3% |

| Maroon | 2 | 2% |

| Orange | 1 | 1% |

| Yellow | 1 | 1% |

| Sums: | 91 | 100% |

If the above sample of 91 students is a good random sample of the population of all students, then we could make a point estimate that roughly 35% of the students in the population will prefer blue.

The mode is the value that occurs most frequently in the data. Spreadsheet programs can determine the mode with the function MODE.

=MODE(data)

In the Fall of 2000 the statistics class gathered data on the number of siblings for each member of the class. One student was an only child and had no siblings. One student had 13 brothers and sisters. The complete data set is as follows:

1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 5, 5, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 12, 13

The mode is 2 because 2 occurs more often than any other value. Where there is a tie there is no mode.

For the ages of students in that class

18, 19, 19, 20, 20, 21, 21, 21, 21, 22, 22, 22, 22, 23, 23, 24, 24, 25, 25, 26

...there is no mode: there is a tie between 21 and 22, hence there no single most frequent value. Spreadsheets will, however, usually report a mode of 21 in this case. Spreadsheets often select the first mode in a multi-modal tie.

If all values appear only once, then there is no mode. Spreadsheets will display #N/A or #VALUE to indicate an error has occurred - there is no mode. No mode is NOT the same as a mode of zero. A mode of zero means that zero is the most frequent data value. Do not put the number 0 (zero) for "no mode." An example of a mode of zero might be the number of children for students in statistics class.

The median is the central (or middle) value in a sorted data set. If a number sits at the middle of a sorted data set, then it is the median. If the middle is between two numbers, then the median is half way between the two middle numbers.

For the sibling data...

1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, |4|, 5, 5, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 12, 13

...the median is 4.

Remember that the data must be in order (sorted) before you can find the median. For the data 2, 4, 6, 8 the median is 5: (4+6)/2.

The median function in spreadsheets is MEDIAN.

=MEDIAN(data)

The mean, also called the arithmetic mean and also called the average, is calculated mathematically by adding the values and then dividing by the number of values (the sample size n).

If the mean is the mean of a population, then it is called the population mean μ. The letter μ is a Greek lower case "m" and is pronounced "mu."

If the mean is the mean of a sample, then it is the sample mean x. The symbol x is pronounced "x bar."

The sum of the data ∑ x can be determined using the function =SUM(data). The sample size n can be determined using =COUNT(data). Thus =SUM(data)/COUNT(data) will calculate the mean. There is also a single function that calculates the mean. The function that directly calculates the mean is AVERAGE

=AVERAGE(data)

Resistant measures: One that is not influenced by extremely high or extremely low data values. The median tends to be more resistant than mean.

If the mean is measured using the whole population then this would be the population mean. If the mean was calculated from a sample then the mean is the sample mean. Mathematically there is no difference in the way the population and sample mean are calculated.

The midrange is the midway point between the minimum and the maximum in a set of data.

To calculate the minimum and maximum values, spreadsheets use the minimum value function MIN and maximum value function MAX.

=MIN(data)

=MAX(data)

The MIN and MAX function can take a list of comma separated numbers or a range of cells in a spreadsheet. If the data is in cells A2 to A42, then the minimum and maximum can be found from:

=MIN(A2:A42)

=MAX(A2:A42)

The midrange can then be calculated from:

midrange = (maximum + minimum)/2

In a spreadsheet use the following formula:

=(MAX(data)+MIN(data))/2

In addition to measures of the middle, measurements of the spread of data values away from the middle are important in statistical analyses. Spread away from the middle usually involves numeric data values. Perhaps the simplest measures of spread away from the middle involve the smallest value, the minimum, and the largest value, the maximum.

The range is the maximum data value minus the minimum data value. The MIN function returns the smallest numeric value in a data set. The MAX functions returns the largest numeric value in a data set. The difference between the maximum value and the minimum value is called the range.

=MAX(data)−MIN(data)

The range is a useful basic statistic that provides information on the distance between the most extreme values in the data set.

The range does not show if the data if evenly spread out across the range or crowded together in just one part of the range. The way in which the data is either spread out or crowded together in a range is referred to as the distribution of the data. One of the ways to understand the distribution of the data is to calculate the position of the quartiles and making a chart based on the results.

The median is the value that is the middle value in a sorted list of values. At the median 50% of the data values are below and 50% are above. This is also called the 50th percentile for being 50% of the way "through" the data.

If one starts at the minimim, 25% of the way "through" the data, the point at which 25% of the values are smaller, is the 25th percentile. The value that is 25% of the way "through" the data is also called the first quartile.

Moving on "through" the data to the median, the median is also called the second quartile.

Moving past the median, 75% of the way "through" the data is the 75th percentile also known as the third quartile.

Note that the 0th quartile is the minimum and the fourth quartile is the maximum.

Spreadsheets can calculate the first, second, and third quartile for data using a function, the quartile function.

=QUARTILE(data,type)

Data is a range with data. Type represents the type of quartile. (0 = 0% or minimum (zeroth quartile), 1 = 25% or first quartile, 2 = 50% or second quartile (also the median), 3 = 75% or third quartile and 4 = 100% or maximum (fourth quartile). Thus if data is in the cells A1:A20, the first quartile could be calculated using:

=QUARTILE(A1:A20,1)

There are some complex subtleties to calculating the quartile. For a full and thorough treatment of the subject refer to Eric Langford's Quartiles in Elementary Statistics, Journal of Statistics Education Volume 14, Number 3 (2006).

The minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum provide a compact and informative five number summary of the distribution of a data set.

The InterQuartile Range (IQR) is the range between the first and third quartile:

=QUARTILE(Data,3) − QUARTILE(Data,1)

There are some subtleties to calculating the IQR for sets with even versus odd sample sizes, but this text leaves those details to the spreadsheet software functions.

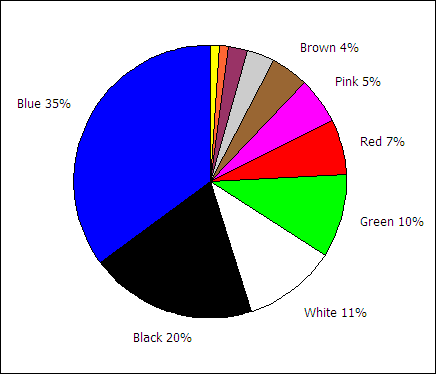

The above is very abstract and hard to visualize. A box and whisker plot takes the above quartile information and plots a chart based on the quartiles. The table below has four different data sets. The first consists of a single value, the second of values spread uniformly across the range, the third has values concentrated near the middle of the range, and the last has most of the values at the minimum or maximum.

| univalue | uniform | peaked symmetric | bimodal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 5 | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| 5 | 7 | 6 | 9 |

| 5 | 8 | 6 | 9 |

| 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

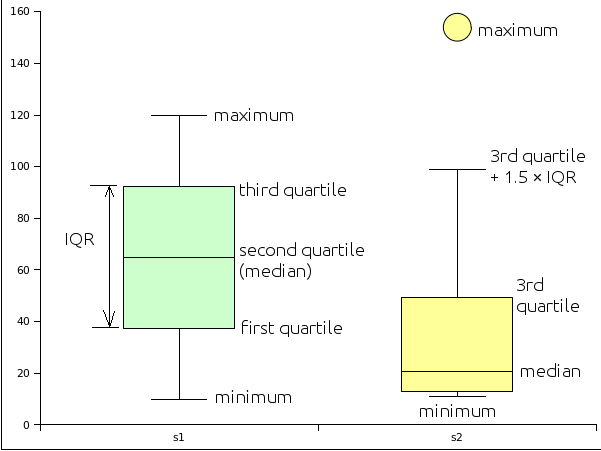

Box plots display how the data is spread across the range based on the quartile information above.

A box and whisker plot is built around a box that runs from the value at the 25th percentile (first quartile) to the value at the 75th percentile (third quartile). The length of the box spans the distance from the value at the first quartile to the third quartile, this is called the Inter-Quartile Range (IQR). A line is drawn inside the box at the location of the 50th percentile. The 50th percentile is also known as the second quartile and is the median for the data. Half the scores are above the median, half are below the median. Note that the 50th percentile is the median, not the mean.

| s1 | s2 |

|---|---|

| 10 | 11 |

| 20 | 11 |

| 30 | 12 |

| 40 | 13 |

| 50 | 15 |

| 60 | 18 |

| 70 | 23 |

| 80 | 31 |

| 90 | 44 |

| 100 | 65 |

| 110 | 99 |

| 120 | 154 |

The basic box plot described above has lines that extend from the first quartile down to the minimum value and from the third quartile to the maximum value. These lines are called "whiskers" and end with a cross-line called a "fence". If, however, the minimum is more than 1.5 × IQR below the first quartile, then the lower fence is put at 1.5 × IQR below the first quartile and the values below the fence are marked with a round circle. These values are referred to as potential outliers - the data is unusually far from the median in relation to the other data in the set.

Likewise, if the maximum is more than 1.5 × IQR beyond the third quartile, then the upper fence is located at 1.5 × IQR above the 3rd quartile. The maximum is then plotted as a potential outlier along with any other data values beyond 1.5 × IQR above the 3rd quartile.

There are actually two types of outliers. Potential outliers between 1.5 × IQR and 3.0 × IQR beyond the fence . Extreme outliers are beyond 3.0 × IQR. In some statistical programs potential outliers are marked with a circle colored in with the color of the box. Extreme outliers are marked with an open circle - a circle with no color inside.

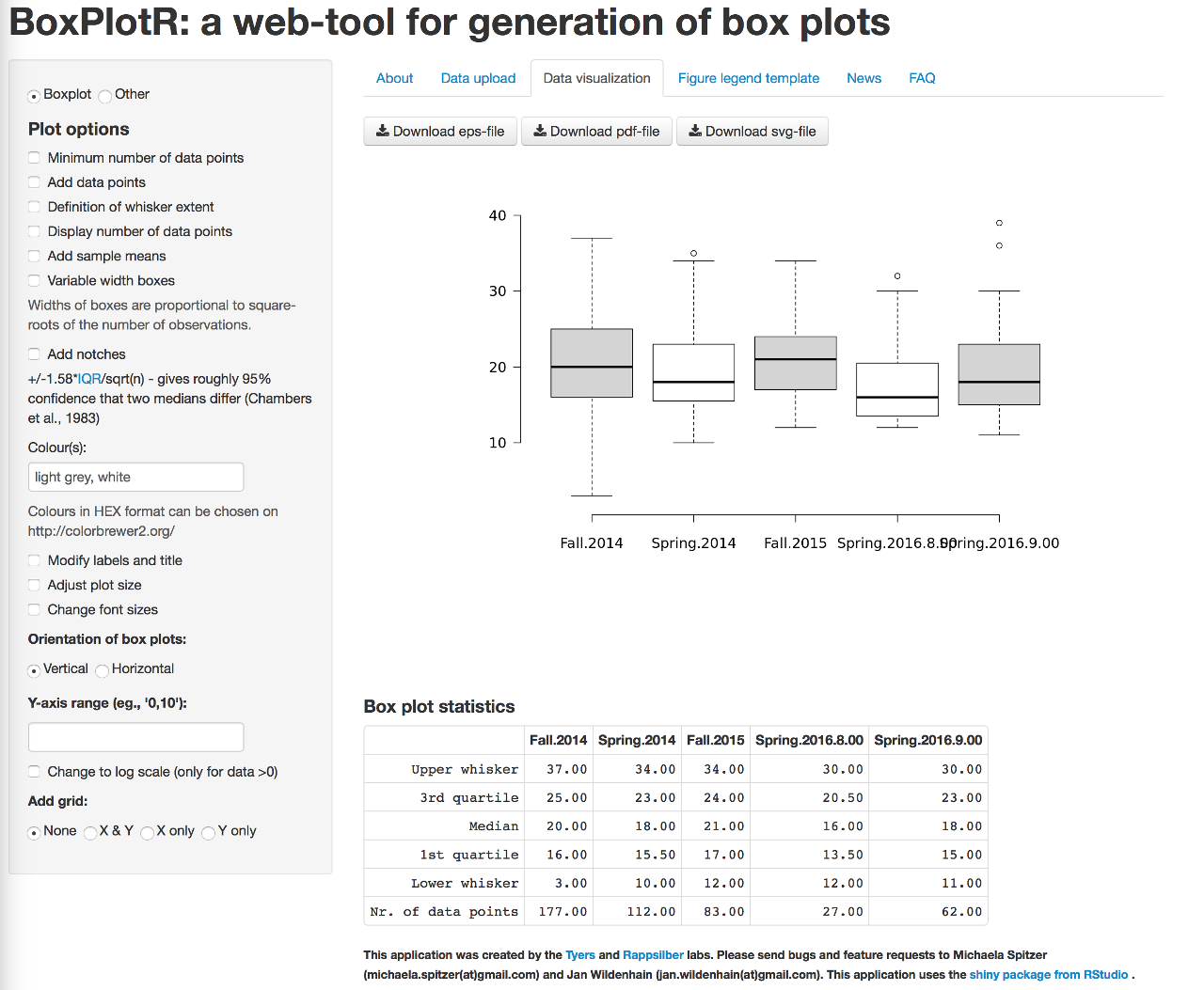

An example with hypothetical data sets is given to illustrate box plots. The data consists of two samples. Sample one (s1) is a uniform distribution and sample two (s2) is a highly skewed distribution.

To generate box plots the online tool BoxPlotR generates box plots including outliers. The first row should be the data label, the variable to be plotted. Data can be copied and pasted into the second tab using the Paste data option. If copying and pasting multiple columns from a spread sheet, preset the separator to Tab. For advanced users notches for the 95% confidence interval for the median can be displayed. The plot can also display the mean and the 95% confidence interval for the mean. The tool is also able to generate violin and bean plots, and change whisker definitions from Tukey to Spear or Altman for advanced users. If the tool grays out, reload the page and recopy the data.

The box and whisker plot is a useful tool for exploring data and determining whether the data is symmetrically distributed, skewed, and whether the data has potential outliers - values far from the rest of the data as measured by the InterQuartile Range. The distribution of the data often impacts what types of analysis can be done on the data.

The distribution is also important to determining whether a measurement that was done is performing as intended. For example, in education a "good" test is usually one that generates a symmetric distribution of scores with few outliers. A highly skewed distribution of scores would suggest that the test was either too easy or too difficult. Outliers would suggest unusual performances on the test.

Consider the following data:

| Data set | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| One | Two | Three | |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| 5 | 9 | 9 | |

| Data set | |||

| One | Two | Three | |

| Mode | 5 | No mode | 1 |

| Median | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mean | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Min | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Max | 5 | 9 | 9 |

Neither the mode, median, nor the mean reveal clearly the differences in the distribution of the data above. The mean and the median are the same for each data set. The mode is the same as the mean and the median for the first data set. Data set two has no mode. Data set three has a tie causing the mode function to select the number closer to the top of the table as the mode. A single number that would characterize how much the data is spread out would be useful.

As noted earlier, the range is one way to capture the spread of the data. The range is calculated by subtracting the smallest value from the largest value. In a spreadsheet:

=MAX(data)−MIN(data)

The range still does not characterize the difference between data sets 2 and 3. In data set two the data is uniformly spread from the minimum to the maximum. Data set three has more data values at the minimum and the maximum. The range misses this difference in the "internal" spread of the data values.

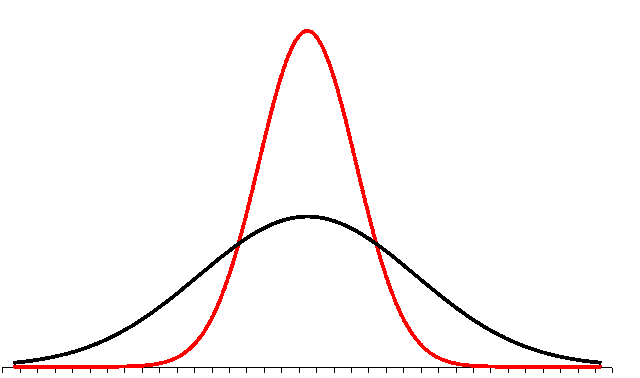

To capture the spread of the data we use a measure related to the average distance of the data from the mean. We call this the standard deviation. If we have a population, we report this average distance as the population standard deviation. If we have a sample, then our average distance value may underestimate the actual population standard deviation. As a result the formula for sample standard deviation adjusts the result mathematically to be slightly larger. For our purposes these numbers are calculated using spreadsheet functions.

One way to distinguish the difference in the distribution of the numbers in data set 2 and data set 3 above is to use the sample standard deviation.

Note that the sample standard deviation well reflects the larger spread seen in data set three.

The mathematical formula for sample the standard deviation is subtracts the mean from each and every data value, squares that difference, adds up the squares, divides by the sample size n minus one, and then takes the square root of the result.

In spreadsheets there is a single function that performs all of the above operations and calculates the sample standard deviation sx, the STDEV function. The STDEV function is the function that will be used in this course.

=STDEV(data)

In this text the symbol for the sample standard deviation in this text is sx.

In this text the symbol for the population standard deviation is the Greek lower case "s": σ.

The symbol sx usually refers the standard deviation of single variable x data. If there is y data, the standard deviation of the y data is sy. Other symbols that are used for standard deviation include s and σx. Some calculators use the unusual and confusing notations σxn−1 and σxn for sample and population standard deviations.

In this class we always use the sample standard deviation in our calculations. The sample standard deviation is calculated in a way such that the sample standard deviation is slightly larger than the result of the formula for the population standard deviation. This adjustment is needed because a population tends to have a slightly larger spread than a sample. There is a greater probability of outliers in the population data.

The Coefficient of Variation is calculated by dividing the standard deviation (usually the sample standard deviation) by the mean.

=STDEV(data)/AVERAGE(data)

Note that the CV can be expressed as a percentage: Group 2 has a CV of 52% while group 3 has a CV of 69%. A deviation of 3.46 is large for a mean of 5 (3.46/5 = 69%) but would be small if the mean were 50 (3.46/50 = 7%). So the CV can tell us how important the standard deviation is relative to the mean.

As an approximation, the standard deviation for data that has a symmetrical, heap-like distribution is roughly one-quarter of the range. If given only minimum and maximum values for data, this rule of thumb can be used to estimate the standard deviation.

At least 75% of the data will be within two standard deviations of the mean, regardless of the shape of the distribution of the data.

At least 89% of the data will be within three standard deviations of the mean, regardless of the shape of the distribution of the data.

If the shape of the distribution of the data is a symmetrical heap, then as much as 95% of the data will be within two standard deviations of the mean.

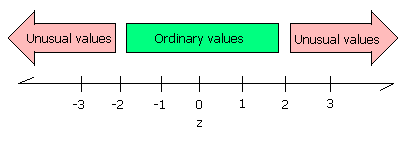

Data beyond two standard deviations away from the mean is considered "unusual" data.

Levels of measurement and appropriate measures

| Level of measurement | Appropriate measure of middle | Appropriate measure of spread |

|---|---|---|

| nominal | mode | none or number of categories |

| ordinal | median | range |

| interval | median or mean | range or standard deviation |

| ratio | mean | standard deviation |

At the interval level of measurement either the median or mean may be more appropriate depending on the specific system being studied. If the median is more appropriate, then the range should be quoted as a measure of the spread of the data. If the mean is more appropriate, then the standard deviation should be used as a measure of the spread of the data.

Another way to understand the levels at which a particular type of measurement can be made is shown in the following table.

Levels at which a particular statistic or parameter has meaning:

| Level of measurement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Ordinal | Interval | Ratio |

| sample size | |||

| mode | |||

| minimum | |||

| maximum | |||

| range | |||

| median | |||

| mean | |||

| standard deviation | |||

| coefficient of variation | |||

For example, a mode, median, and mean can be calculated for ratio level measures. Of those, the mean is usually considered the best measure of the middle for a random sample of ratio level data.

A variable is defined as any measurement that can take on different data values. Variables are named containers for data values. In statistics variables are often words such as marble color, leaflet length, or marble position.

In a spreadsheet, variables are usually put in row one with the data in the rows below row one. A variable can also have units of measure.

Variables are said to be at the type and level of measurement of the data that the variable contains. Thus variables can be qualitative or quantitative, discrete or continuous. Variables can be at the nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio level of measurement.

When there are a countable number of values that result from observations, we say the variable producing the results is discrete. The nominal and ordinal levels of measurement almost always measure a discrete variable.

The following examples are typical values for discrete variables:

The last example above is a typical result of a type of survey called a Likert survey developed by Renis Likert in 1932.

When reporting the "middle value" for a discrete distribution at the ordinal level it is usually more appropriate to report the median. For further reading on the matter of using mean values with discrete distributions refer to the pages by Nora Mogey and by the Canadian Psychiatric Association.

Note that if the variable measures only the nominal level of measurement, then only the mode is likely to have any statistical "meaning", the nominal level of measurement has no "middle" per se.

There may be rare instances in which looking at the mean value and standard deviation is useful for looking at comparative performance, but it is not a recommended practice to use the mean and standard deviation on a discrete distribution. The Canadian Psychiatric Association discusses when one may be able to "break" the rules and calculate a mean on a discrete distribution. Even then, bear in mind that ratios between means have no "meaning!"

For example, questionnaire's often generate discrete results:

There are only four possible results for each question. Numeric values (0, 1, 2, 3) could be assigned to the four results, but the numbers would have no particular direct meaning. For example, if the average was 2.5, that would not translate back to a specific number of days per week of usage.

When there is a infinite (or uncountable) number of values that may result from observations, we say that the variable is continuous. Physical measurements such as height, weight, speed, and mass, are considered continuous measurements. Bear in mind that our measurement device might be accurate to only a certain number of decimal places. The variable is continuous because better measuring devices should produce more accurate results.

The following examples are continuous variables:

When reporting the "middle value" for a continuous distribution it is most often appropriate to report the mean and standard deviation. The mean and standard deviation only have "meaning" for the ratio level of measurement.

| Level of measurement | Typical variable type | Typical measure of middle | Typical measure of variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| nominal | discrete | mode | none |

| ordinal | discrete | median | range |

| interval | discrete | median | range |

| ratio | continuous | mean* | sample standard deviation |

*For some ratio level data sets the median may be preferable to the mean. If outliers are known to be likely to be errors in measurement, then the median can produce a better estimate of the middle of a data set.

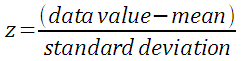

Z-scores are a useful way to compare or combine scores from data that has different means and standard deviations. Z-scores are an application of the above measures of middle and spread.

Remember that the mean is the result of adding all of the values in the data set and then dividing by the number of values in the data set. The word mean and average are used interchangeably in statistics.

Recall also that the sample standard deviation can be thought of as a mathematical calculation of the average distance of the data from the mean of the data. Note that although I use the words average and mean, the sentence could also be written "the mean distance of the data from the mean of the data."

Z-scores simply indicate how many standard deviations away from the mean is a particular data value. This is termed "relative standing" as it is a measure of where in the data the particular data value is located relative to the mean as counted in units of standard deviations. The formula for calculating the z-score is:

If the population mean µ and population standard deviation σ are known, then the formula for the z-score for a data value x is:

Using the sample mean x and sample standard deviation sx, the formula for a data value x is:

Note the parentheses! When typing in a spreadsheet do not forget the parentheses.

=(value−AVERAGE(data))/STDEV(data)

Data that is two standard deviations below the mean will have a z-score of −2, data that is two standard deviations above the mean will have a z-score of +2. Data beyond two standard deviations away from the mean will have z-scores below −2 or above 2. A data value that has a z-score below −2 or above +2 is considered an unusual value, an extraordinary data value. These values may also be outliers on a box plot depending on the distribution. Box plot outliers and extraordinary z-scores are two ways to characterize unusually extreme data values. There is no simple relationship between box plot outliers and extraordinary z-scores.

Suppose a test has a mean score of 10 and a standard deviation of 2 with a total possible of 20. Suppose a second test has the same mean of 10 and total possible of 20 but a standard deviation of 8.

On the first test a score of 18 would be rare, an unusual score. On the first test 89% of the students would have scored between 6 and 16 (three standard deviations below the mean and three standard deviations above the mean.

On the second test a score of 18 would only be one standard deviation above the mean. This would not be unusual, the second test had more spread.

Adding two scores of 18 and saying the student had a score of 36 out of 40 devalues what is a phenomenal performance on the first test.

Converting to z-scores, the relative strength of the performance on test one is valued more strongly. The z-score on test one would be (18-10)/2 = 4, while on test two the z-score would be (18-10)/8 = 1. The unusually outstanding performance on test one is now reflected in the sum of the z-scores where the first test contributes a sum of 4 and the second test contributes a sum of 1.

When values are converted to z-scores, the mean of the z-scores is zero. A student who scored a 10 on either of the tests above would have a z-score of 0. In the world of z-scores, a zero is average!

Z-scores also adjust for different means due to differing total possible points on different tests.

Consider again the first test that had a mean score of 10 and a standard deviation of 2 with a total possible of 20. Now consider a third test with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 40 with a total possible of 200. On this third test a score of 140 would be high, but not unusually high.

Adding the scores and saying the student had a score of 158 out of 220 again devalues what is a phenomenal performance on test one. The score on test one is dwarfed by the total possible on test three. Put another way, the 18 points of test one are contributing only 11% of the 158 score. The other 89% is the test three score. We are giving an eight-fold greater weight to test three. The z-scores of 4 and 1 would add to five. This gives equal weight to each test and the resulting sum of the z-scores reflects the strong performance on test one with an equal weight to the ordinary performance on test three.

Z-scores only provide the relative standing. If a test is given again and all students who take the test do better the second time, then the mean rises and like a tide "lifts all the boats equally." Thus an individual student might do better, but because the mean rose, their z-score could remain the same. This is also the downside to using z-scores to compare performances between tests - changes in "sea level" are obscured. One would have to know the mean and standard deviation and whether they changed to properly interpret a z-score.

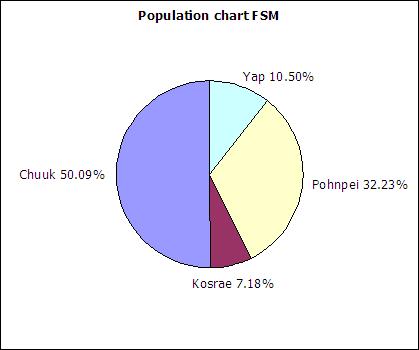

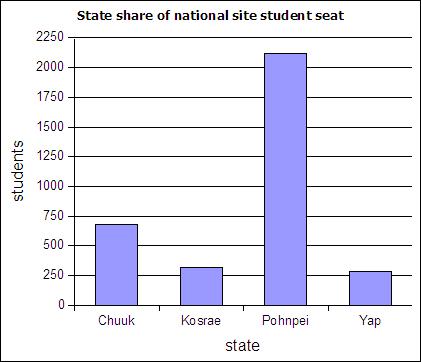

The table below includes FSM census 2000 data and student seat numbers for the national site of COM-FSM circa 2004.

| State | Population (2000) | Fractional share of national population (relative frequency) | Number of student seats held by state at the national campus | Fractional share of the national campus student seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuuk | 53595 | 0.5 | 679 | 0.2 |

| Kosrae | 7686 | 0.07 | 316 | 0.09 |

| Pohnpei | 34486 | 0.32 | 2122 | 0.62 |

| Yap | 11241 | 0.11 | 287 | 0.08 |

| 107008 | 1 | 3404 | 1 |

In a circle chart the whole circle is 100% Used when data adds to a whole, e.g. state populations add to yield national population.

A pie chart of the state populations:

The following table includes data from the 2010 FSM census as an update to the above data.

| State | Population (2010) | Relative frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Chuuk | 48651 | |

| Kosrae | 6616 | |

| Pohnpei | 35981 | |

| Yap | 11376 | |

| Sum: | 102624 |

Column charts are also called bar graphs. A column chart of the student seats held by each state at the national site:

If a column chart is sorted so that the columns are in descending order, then it is called a Pareto chart. Descending order means the largest value is on the left and the values decrease as one moves to the right. Pareto charts are useful ways to convey rank order as well as numerical data.

A line graph is a chart which plots data as a line. The horizontal axis is usually set up with equal intervals. Line graphs are not used in this course and should not be confused with xy scattergraphs.

When you have two sets of continuous data (value versus value, no categories), use an xy graph. These will be covered in more detail in the chapter on linear regressions.

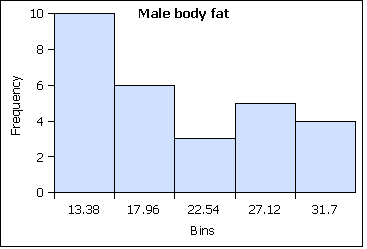

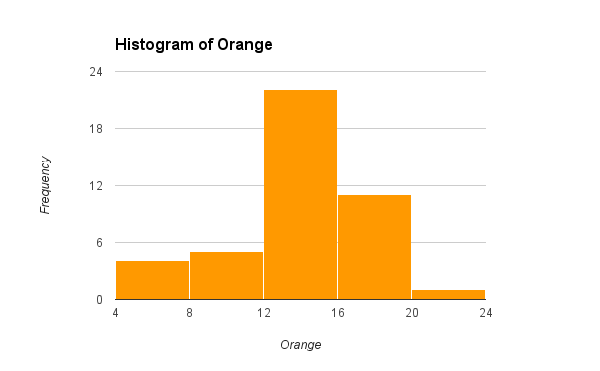

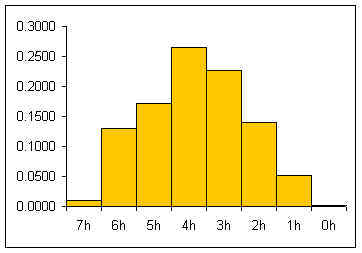

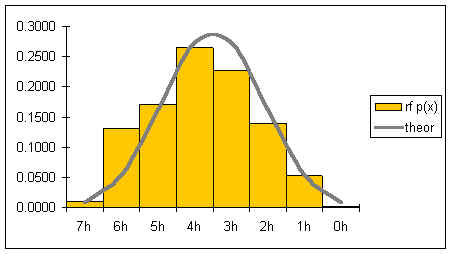

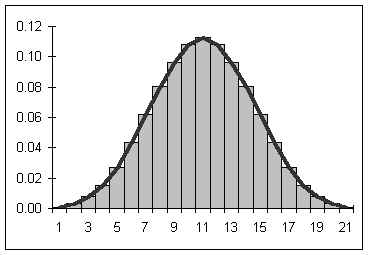

A distribution counts the number of elements of data in either a category or within a range of values. Plotting the count of the elements in each category or range as a column chart generates a chart called a histogram. The histogram shows the distribution of the data. The height of each column shows the frequency of an event. This distribution often provides insight into the data that the data itself does not reveal. In the histogram below, the distribution for male body fat among statistics students has two peaks. The two peaks suggest that there are two subgroups among the men in the statistics course, one subgroup that is at a healthy level of body fat and a second subgroup at a higher level of body fat.

The ranges into which values are gathered are called bins, classes, or intervals. This text tends to use classes or bins to describe the ranges into which the data values are grouped.

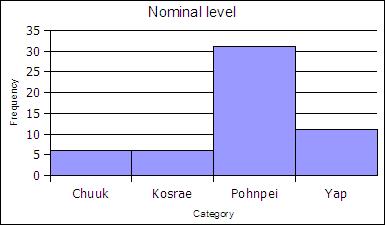

At the nominal level of measurement one can determine the frequency of elements in a category, such as students by state in a statistics course.

| State | Frequency | Relative Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Chuuk | 6 | 0.11 |

| Kosrae | 6 | 0.11 |

| Pohnpei | 31 | 0.57 |

| Yap | 11 | 0.20 |

| Sums: | 54 | 1.00 |

The sum of the frequencies is the sample size.

The sum of the relative frequencies is always one.

The sum of the frequencies being the sample size and the sum of the relative frequencies being one are ways to check your frequency table.

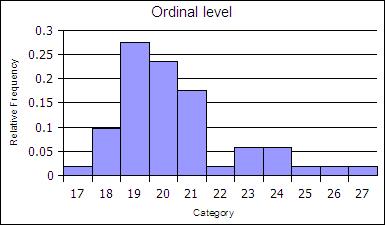

At the ordinal level, a frequency distribution can be done using the rank order, counting the number of elements in each rank order to obtain a frequency. When the frequency data is calculated in this way, the distribution is not grouped into a smaller number of classes. Note that some classes could be empty - the classes must still be equal width.

| Age | Frequency | Rel Freq |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 18 | 5 | 0.1 |

| 19 | 14 | 0.27 |

| 20 | 12 | 0.24 |

| 21 | 9 | 0.18 |

| 22 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 23 | 3 | 0.06 |

| 24 | 3 | 0.06 |

| 25 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 26 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 27 | 1 | 0.02 |

| sums | 51 | 1 |

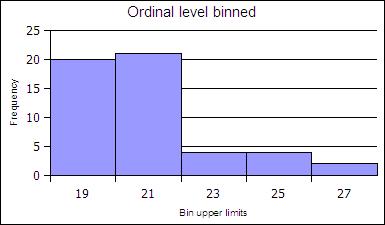

The ranks can be collected together, classed, to reduce the number of rank order categories. in the example below the age data in gathered into two-year cohorts.

| Age | Frequency | Rel Freq |

|---|---|---|

| 19 | 20 | 0.39 |

| 21 | 21 | 0.41 |

| 23 | 4 | 0.08 |

| 25 | 4 | 0.08 |

| 27 | 2 | 0.04 |

| Sums: | 51 | 1 |

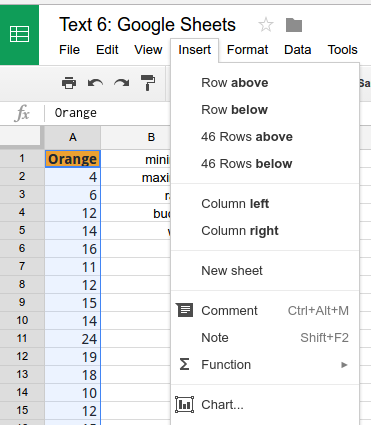

Ratio level data is usually a continuous variable. The number of possible values cannot be counted. At the ratio level data is divided into intervals of equal width from the minimum value to the maximum value. The intervals are called classes by statisticians. The intervals are called buckets in Google Sheets™.

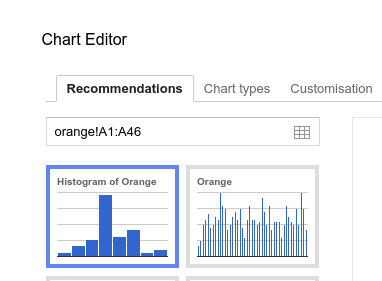

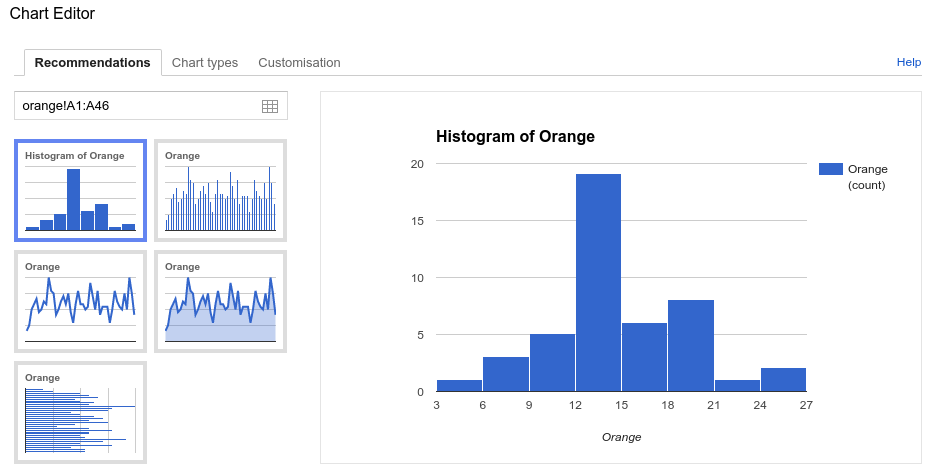

Google Sheets™ can automatically generate a histogram chart from raw data. The specific dialog boxes tend to change in terms of layout and new edit capabilities appear over time.

Pre-select the data range and from the Insert menu choose Chart.

Choose the histogram chart option.

At this point the histogram chart could be inserted into the spread sheet using the automatically chosen number of classes (buckets).

Google Sheets™ also provides the option to specify the number of classes (buckets).

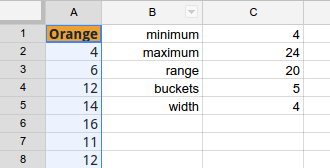

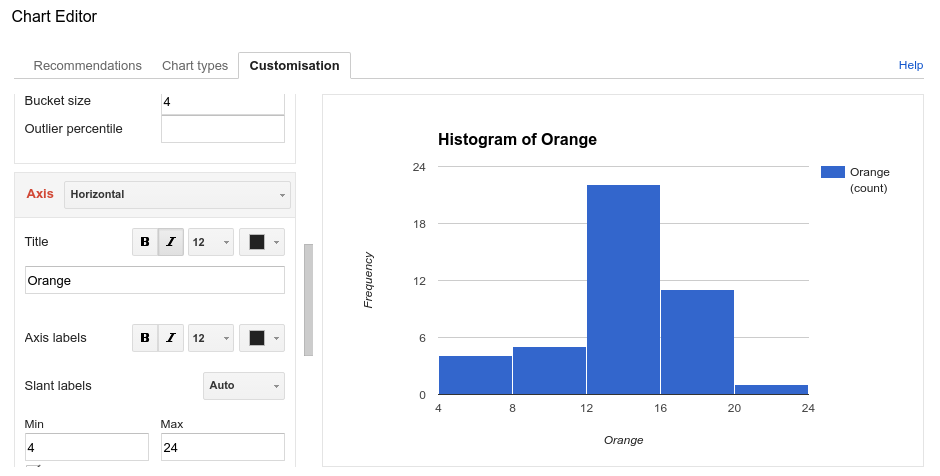

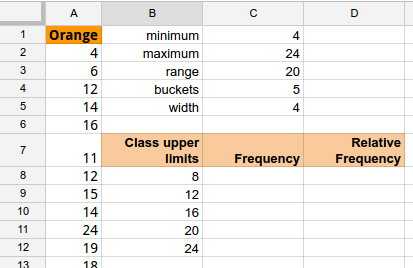

To generate a histogram with a specific number of classes, determine the minimum, maximum, and range. Divide the range by the number of desired classes (buckets) to obtain the class width. In the following example a five bucket histogram chart was desired.

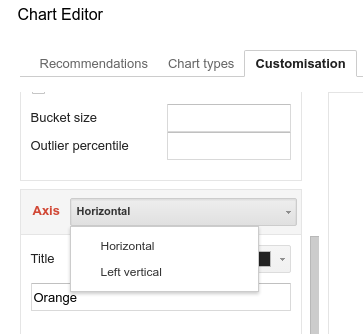

With the Axis set to Horizontal...

Enter the width as the bucket size. Further below enter the minimum value, and maximum values.

Insert.

Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

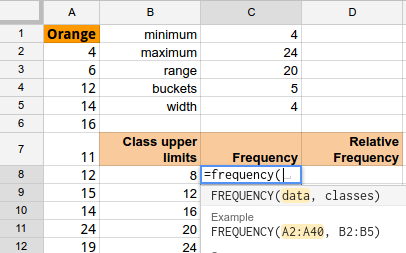

Each bucket has a smallest value called the class lower limit. Each bucket has a largest value called a class upper limit. The number of data values in each bucket is called the frequency. Spreadsheets have a FREQUENCY function that uses the class upper limits to automatically count the frequencies for each bucket.

To calculate the class upper limits the minimum and maximum value in a data set must be determined. Spreadsheets include functions to calculate the minimum value MIN and maximum value MAX in a data set.

=MIN(data)

=MAX(data)

The minimum and maximum are used to calculate the range. The width of each bucket is equal to the range divided by the number of desired buckets.

| Class Upper Limits (CUL) | Frequency |

| =min + class width | |

| + class width | |

| + class width | |

| + class width | |

| + class width = max |

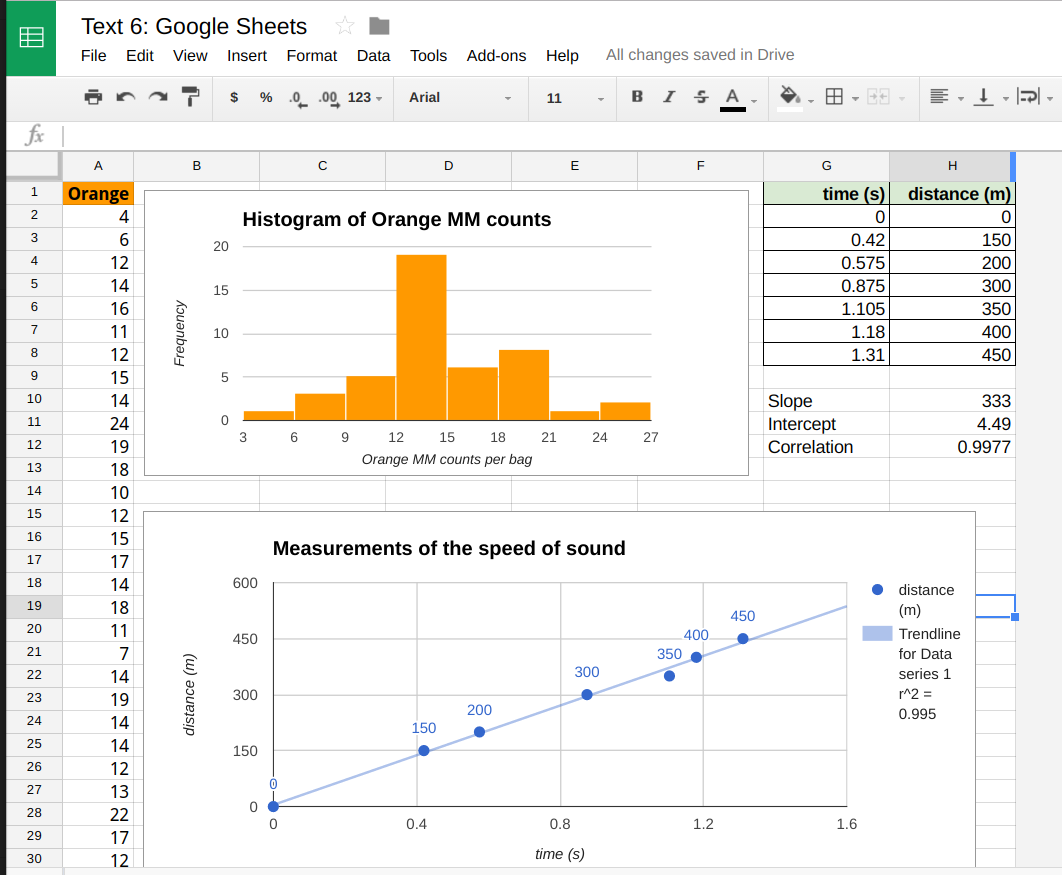

For the Orange MM data determine the minimum and maximum. Calculate the range. For a five class (bucket) frequency table, divide the range by five to obtain the width. Use the table above to enter the class upper limits.

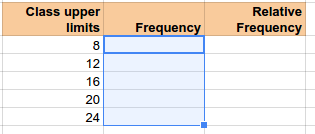

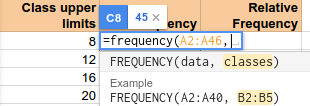

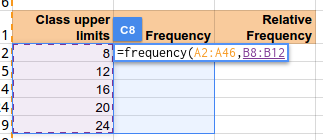

Pre-select the cells into which the FREQUENCY array function will place the frequencies. Note that one selects all of the cells before typing the formula!

Then enter the formula.

Select or type in the spreadsheet addresses containing the data.

Type a comma, and then enter the spreadsheet addresses containing the class upper limits.

Close the parentheses and press enter.

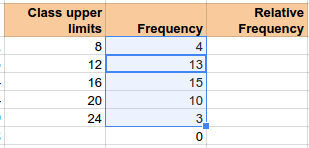

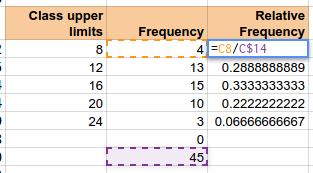

Relative frequencies can be added in a third column.

As noted above:

The sum of the frequencies is the sample size.

The sum of the relative frequencies is always one.

The sum of the frequencies being the sample size and the sum of the relative frequencies being one are ways to check your frequency table.

Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

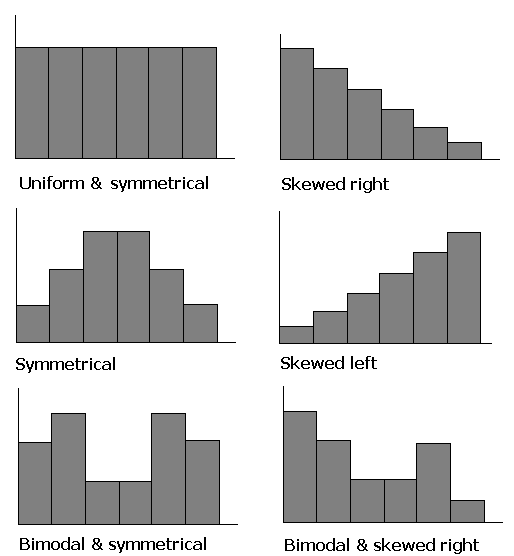

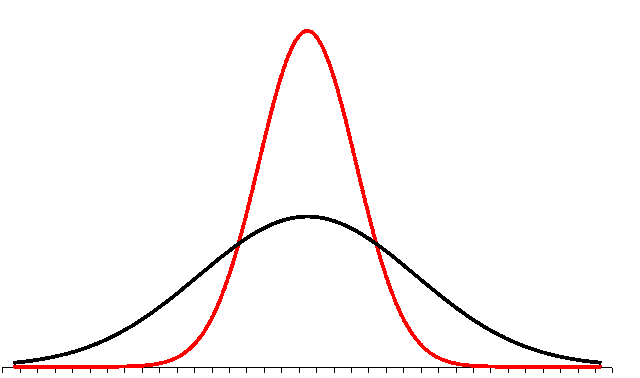

The shapes of distributions have names by which they are known.

One of the aspects of a sample that is often similar to the population is the shape of the distribution. If a good random sample of sufficient size has a symmetric distribution, then the population is likely to have a symmetric distribution. The process of projecting results from a sample to a population is called generalizing. Thus we can say that the shape of a sample distribution generalizes to a population.

| uniform | peaked symmetric | skewed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | 7 | 8 |

| 4 | 9 | 9 |

| 5 | 10 | 11 |

| 6 | 11 | 12 |

| 7 | 12 | 13 |

| 8 | 12 | 14 |

| 9 | 13 | 15 |

| 10 | 13 | 16 |

| 11 | 14 | 17 |

| 12 | 14 | 18 |

| 13 | 14 | 19 |

| 14 | 14 | 20 |

| 15 | 15 | 20 |

| 16 | 15 | 21 |

| 17 | 15 | 22 |

| 18 | 15 | 23 |

| 19 | 16 | 24 |

| 20 | 16 | 23 |

| 21 | 17 | 24 |

| 22 | 17 | 25 |

| 23 | 18 | 26 |

| 24 | 19 | 27 |

| 25 | 20 | 25 |

| 26 | 22 | 26 |

| 27 | 24 | 27 |

| 28 | 28 | 28 |

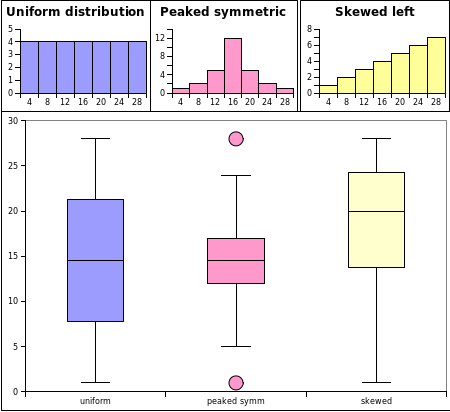

Both box plots and frequency histograms show the distribution of the data. Box plots and frequency histograms are two different views of the distribution of the data. There is a relationship between the frequency histogram and the associated box plot. The following charts show the frequency histograms and box plots for three distributions: a uniform distribution, a peaked symmetric heap distribution, and a left skewed distribution.

The uniform data is evenly distributed across the range. The whiskers run from the maximum to minimum value and the InterQuartile Range is the largest of the three distributions.

The peaked symmetric data has the smallest InterQuartile Range, the bulk of the data is close to the middle of the distribution. In the box plot this can be seen in the small InterQuartile range centered on the median. The peaked symmetric data has two potential outliers at the minimum and maximum values. For the peaked symmetric distribution data is usually found near the middle of the distribution.

The skewed data has the bulk of the data near the maximum. In the box plot this can be seen by the InterQuartile Range - the box - being "pushed" up towards the maximum value. The whiskers are also of an unequal length, another sign of a skewed distribution.

Some distributions are considered "pathological" in the sense that they are not statistically "well-behaved." Such distributions are problematic for the normal curve statistical analyses that are done later in this course. For example, two highly skewed distributions with extreme outliers can have the same mean but a different median. The pathology of the two data sets is a result of the impact of outliers on the mean. Outliers do not impact the median as much as they do the mean. Hence the mean is said to be sensitive to outliers while the median is said to be insensitive to outliers.

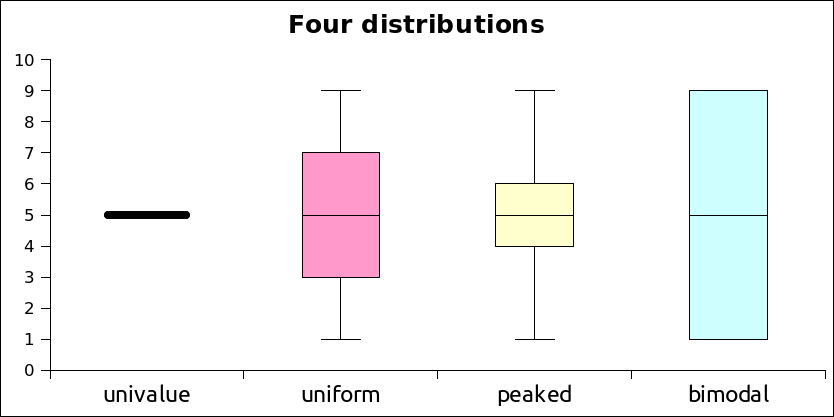

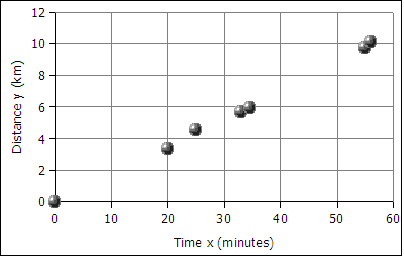

A runner runs from the College of Micronesia-FSM National campus to PICS via the powerplant/Nanpohnmal back road. The runner tracks his time and distance.

| Location | Time x (minutes) | Distance y (km) |

|---|---|---|

| College | 0 | 0 |

| Dolon Pass | 20 | 3.3 |

| Turn-off for Nanpohnmal | 25 | 4.5 |

| Bottom of the beast | 33 | 5.7 |

| Top of the beast | 34.5 | 5.9 |

| Track West | 55 | 9.7 |

| PICS | 56 | 10.1 |

Is there a relationship between the time and the distance? If there is a relationship,

then data will fall in a patterned fashion on an xy graph. If there is no relationship,

then there will be no shape to the pattern of the data on a graph.

If the relationship is linear, then the data will fall roughly along a line. Plotting the

above data yields the following graph:

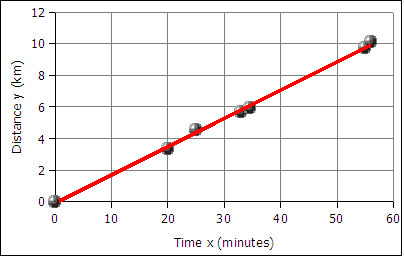

The data falls roughly along a line, the relationship appears to linear. If we can find the equation of a line through the data, then we can use the equation to predict how long it will take the runner to cover distances not included in the table above, such as five kilometers. In the next image a best fit line has been added to the graph.

The best fit line is also called the least squares line because the mathematical process for determining the line minimizes the square of the vertical displacement of the data points from the line. The process of determining the best fit line is also known and performing a linear regression. Sometimes the line is referred to as a linear regression.

The graph of time versus distance for a runner is a line because a runner runs at the same pace kilometer after kilometer.

For paired data the sample size n is the number of pairs. This is usually also the number of rows in the data table. Do NOT count both the x and y values, the (x,y) data should be counted in pairs.

A spreadsheet is used to find the slope and the y-intercept of the best fit line through the data.

To get the slope m use the function:

=SLOPE(y-values,x-values)

Note that the y-values are entered first, the x-values are entered second. This is the reverse of traditional algebraic order where coordinate pairs are listed in the order (x, y). The x and y-values are usually arranged in columns. The column containing the x data is usually to the left of the column containing the y-values. An example where the data is in the first two columns from row two to forty-two can be seen below.

=SLOPE(B2:B42,A2:A42)

The intercept is usually the starting value for a function. Often this is the y data value at time zero, or distance zero.

To get the intercept:

=INTERCEPT(y-values,x-values)

Note that intercept also reverses the order of the x and y values!

For the runner data above the equation is:

distance = slope * time + y-intercept

distance = 0.18 * time + − 0.13

y = 0.18 * x + − 0.13

or

y = 0.18x − 0.13

where x is the time and y is the distance

In algebra the equation of a line is written as y = m*x + b where m is the slope and b is the intercept. In statistics the equation of a line is written as y = a + b*x where a is the intercept (the starting value) and b is the slope. The two fields have their own traditions, and the letters used for slope and intercept are a tradition that differs between the field of mathematics and the field of statistics.

Using the y = mx + b equation we can make predictions about how far the runner will travel given a time, or how long a duration of time the runner will run given a distance. For example, according the equation above, a 45 minute run will result in the runner covering 0.18*45 - 0.13 = 7.97 kilometers. Using the inverse of the equation we can predict that the runner will run a five kilometer distance in 28.5 minutes (28 minutes and 30 seconds).

Given any time, we can calculate the distance. Given any distance, we can solve for the time.

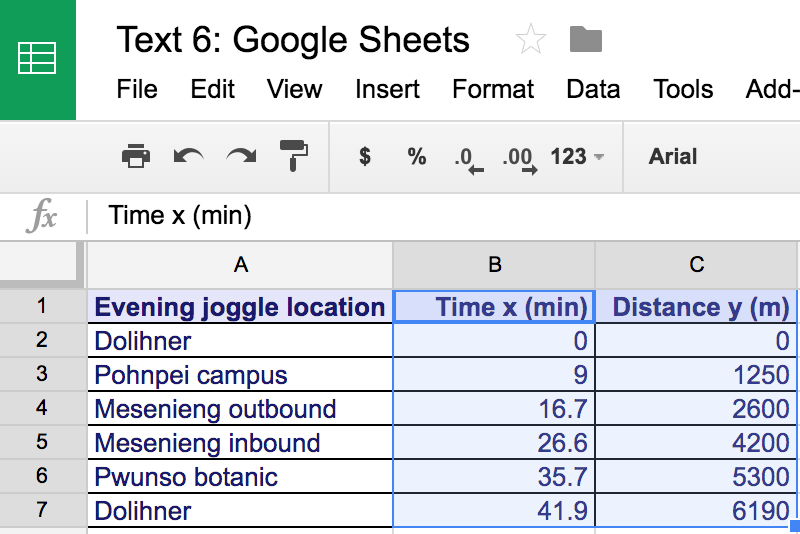

The data used in the following examples is contained in the following table.

| Evening joggle (run+juggle) location | Time x (min) | Distance y (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Dolihner | 0.0 | 0 |

| Pohnpei campus | 9.0 | 1250 |

| Mesenieng outbound | 16.7 | 2600 |

| Mesenieng inbound | 26.6 | 4200 |

| Pwunso botanic | 35.7 | 5300 |

| Dolihner | 41.9 | 6190 |

First select the data to be graphed.

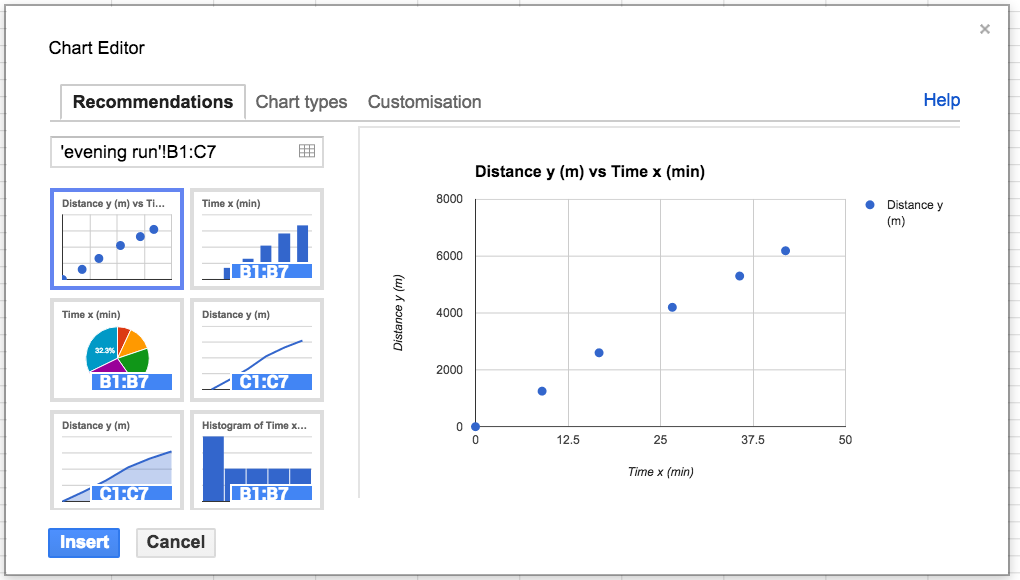

Choose either Insert: Chart or click on the Insert Chart icon on the menubar.

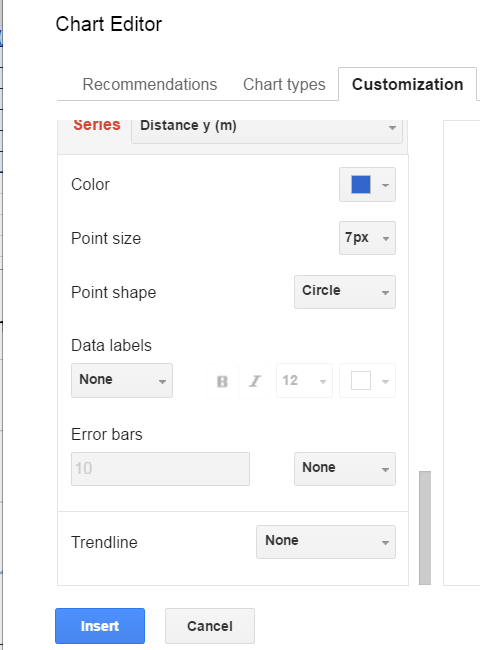

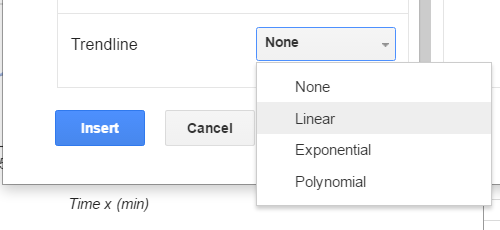

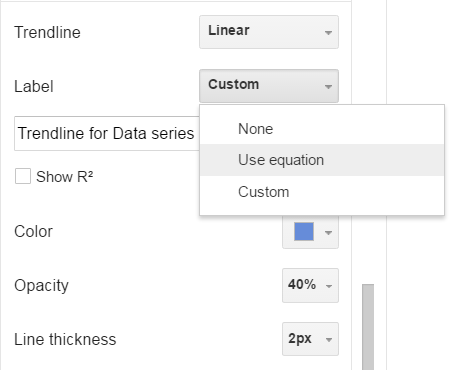

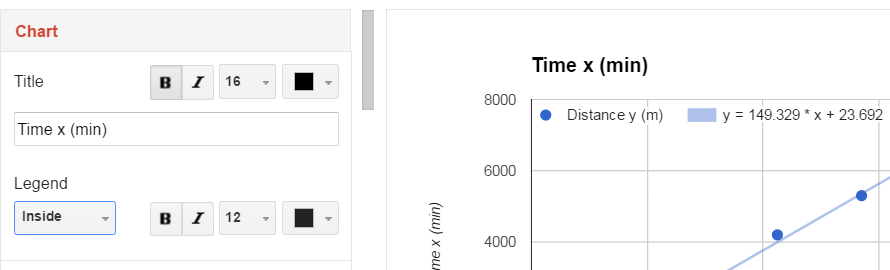

Choose the xy scatter graph in the Chart Editor. The chart editor's third tab, Customization, can be used to display the equation of the line. The trendline options are at the bottom of the dialog box.

Options include linear, exponential, and polynomial. In this text linear trendlines are used.

Once the linear option is chosen, the dialog box expands to show other options including displaying the trendline and R². R² is covered later in this chapter.

The location of the legend can also be selected to "unwrap" the equation of the line. In some legend locations the legend might not display both the equation and the R² value.

Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

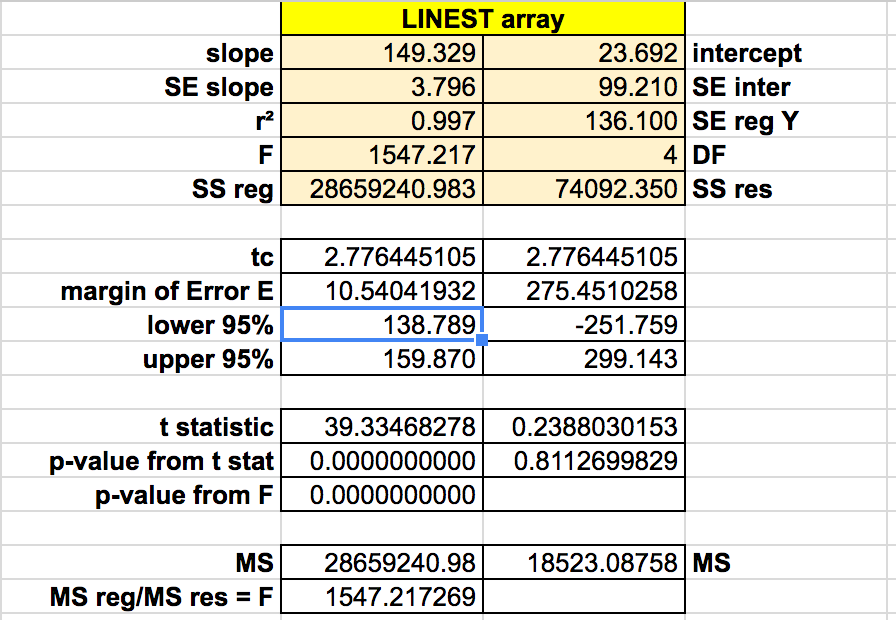

The LINEST array function in Google Sheets™ can be used, =LINEST(y-data,x-data,true,true) to obtain the statistics necessary to construct 95% confidence intervals for the slope and intercept. This example uses the same evening run data provided above.

After plotting the x and y data, the xy scattergraph helps determine the nature of the relationship between the x values and the y values. If the points lie along a straight line, then the relationship is linear. If the points form a smooth curve, then the relationship is non-linear (not a line). If the points form no pattern then the relationship is random.

Relationships between two sets of data can be positive: the larger x gets, the larger y

gets.

Relationships between two sets of data can be negative: the larger x gets, the smaller y

gets.

Relationships between two sets of data can be non-linear

Relationships between two sets of data can be random: no relationship exists!

For the runner data above, the relationship is a positive relationship. The points line along a line, therefore the relationship is linear.

An example of a negative relationship would be the number of beers consumed by a student and a measure of the physical coordination. The more beers consumed the less their coordination!

For a linear relationship, the closer to a straight line the points fall, the stronger the relationship. The measurement that describes how closely to a line are the points is called the correlation.

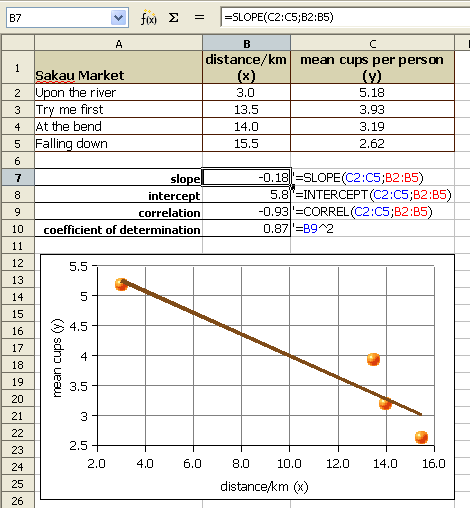

The following example explores the correlation between the distance of a business from a city center versus the amount of product sold per person. In this case the business are places that serve pounded Piper methysticum plant roots, known elsewhere as kava but known locally as sakau. This business is unique in that customers self-limit their purchases, buying only as many cups of sakau as necessary to get the warm, sleepy, feeling that the drink induces. The businesses are locally referred to as sakau markets. The local theory is that the further one travels from the main town (and thus deeper into the countryside of Pohnpei) the stronger the sakau that is served. If this is the case, then the mean number of cups should fall with distance from the main town on the island.

The following table uses actual data collected from these businesses, the names of the businesses have been changed.

| Sakau Market | distance/km (x) | mean cups per person (y) |

|---|---|---|

| Upon the river | 3.0 | 5.18 |

| Try me first | 13.5 | 3.93 |

| At the bend | 14.0 | 3.19 |

| Falling down | 15.5 | 2.62 |

The first question a statistician would ask is whether there is a relationship between the distance and mean cup data. Determining whether there is a relationship is best seen in an xy scattergraph of the data.

If we plot the points on an xy graph using a spreadsheet, the y-values can be seen to fall with increasing x-value. The data points, while not all exactly on one line, are not far away from the best fit line. The best fit line indicates a negative relationship. The larger the distance, the smaller the mean number of cups consumed.

We use a number called the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient r to tell us how well the data fits to a straight line. The full name is long, in statistics this number is called simply r. R can be calculated using a spreadsheet function.

The function for calculating r is:

=CORREL(y-values,x-values)

Note that the order does not technically matter. The correlation of x to y is the same as that of y to x. For consistency the y-data,x-data order is retained above.

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient r (or just correlation r) values that result from the formula are always between -1 and 1. One is perfect positive linear correlation. Negative one is perfect negative linear correlation. If the correlation is zero or close to zero: no linear relationship between the variables.

A guideline to r values:

Note that perfect has to be perfect: 0.99999 is very close, but not perfect. In real world systems perfect correlation, positive or negative, is rarely or never seen. A correlation of 0.0000 is also rare. Systems that are purely random are also rarely seen in the real world.

Spreadsheets usually round to two decimals when displaying decimal numbers. A correlation r of 0.999 is displayed as "1" by spreadsheets. Use the Format menu to select the cells item. In the cells dialog box, click on the numbers tab to increase the number of decimal places. When the correlation is not perfect, adjust the decimal display and write out all the decimals.

The correlation r of − 0.93 is a strong negative correlation. The relationship is strong and the relationship is negative. The equation of the best fit line, y = −0.18x + 5.8 where y is the mean number of cups and x is the distance from the main town. The equations that generated the slope, y-intercept, and correlation can be seen in the earlier image.

The strong relationship means that the equation can be used to predict mean cup values, at least for distances between 3.0 and 15.5 kilometers from town.

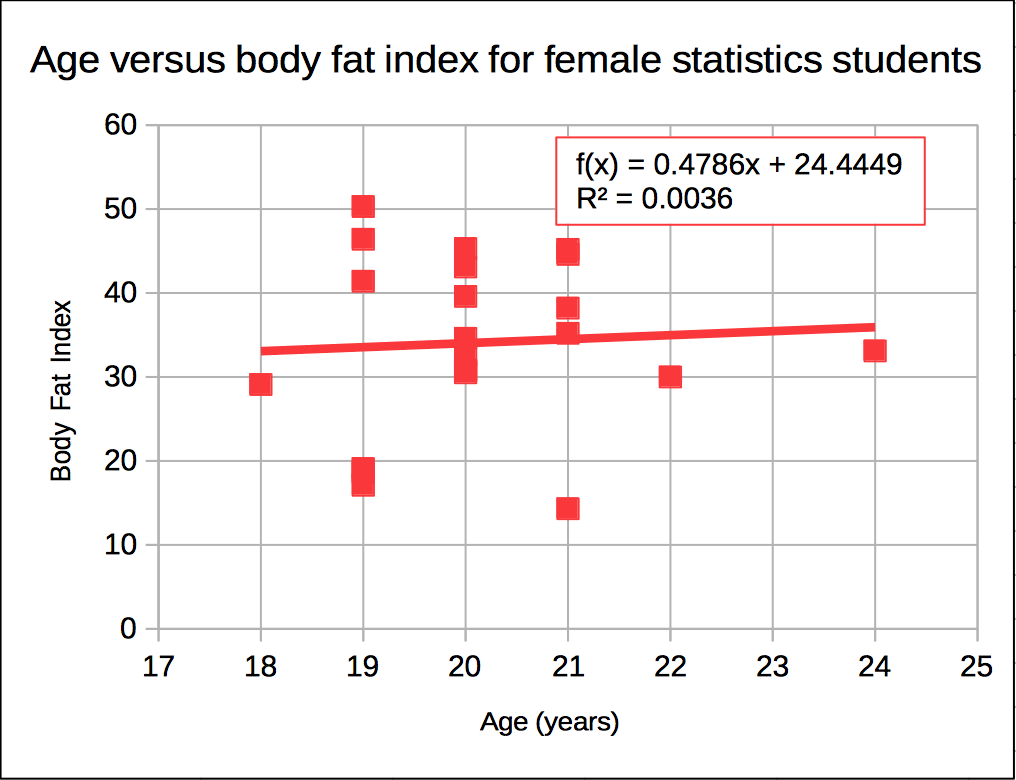

A second example is drawn from body fat data. The following chart plots age in years for female statistics students against their body fat index.

Is there a relationship seen in the xy scattergraph between the age of a female statistics student and the body fat index? Can we use the equation to predict body fat index on age alone?

If we plot the points on an xy graph using a spreadsheet as seen above, the data does not appear to be linear. The data points do not form a discernable pattern. The data appears to be scattered randomly about the graph. Although a spreadsheet is able to give us a best fit line (a linear regression or least squares line), that equation will not be useful for predicting body fat index based on age.

In the example above the correlation r can be calculated and is found to be 0.06. Zero would be random correlation. This value is so close to zero that the correlation is effectively random. The relationship is random. There is no relationship. The linear equation cannot be used to predict the body fat index given the age.

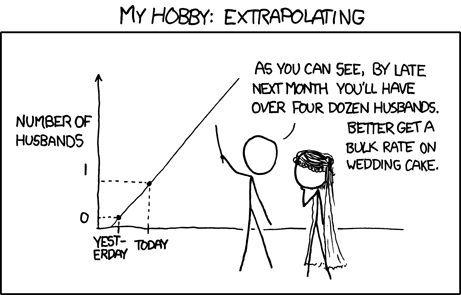

We cannot usually predict values that are below the minimum x or above the maximum x values and make meaningful predictions. In the example of the runner, we could calculate how far the runner would run in 72 hours (three days and three nights) but it is unlikely the runner could run continuously for that length of time. For some systems values can be predicted below the minimum x or above the maximum x value. When we do this it is called extrapolation. Very few systems can be extrapolated, but some systems remain linear for values near to the provided x values.

Image credit: xkcd under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 license. Some rights reserved.

The coefficient of determination, r², is a measure of how much of the variation in the independent x variable explains the variation in the dependent y variable. This does NOT imply causation. In spreadsheets the ^ symbol (shift-6) is exponentiation. In spreadsheets we can square the correlation with the following formula:

=(CORREL(y-values,x-values))^2

The result, which is between 0 and 1 inclusive, is often expressed as a percentage.

Imagine a Yamaha outboard motor fishing boat sitting out beyond the reef in an open ocean swell. The swell moves the boat gently up and down. Now suppose there is a small boy moving around in the boat. The boat is rocked and swayed by the boy. The total motion of the boat is in part due to the swell and in part due to the boy. Maybe the swell accounts for 70% of the boat's motion while the boy accounts for 30% of the motion. A model of the boat's motion that took into account only the motion of the ocean would generate a coefficient of determination of about 70%.

Finding that a correlation exists does not mean that the x-values cause the y-values. A line does not imply causation: Your age does not cause your pounds of body fat, nor does time cause distance for the runner.

Studies in the mid 1800s of Micronesia would have shown of increase each year in church attendance and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). That does NOT mean churches cause STDs! What the data is revealing is a common variable underlying our data: foreigners brought both STDs and churches. Any correlation is simply the result of the common impact of the increasing influence of foreigners.

Some calculators will generate a best fit line. Be careful. In algebra straight lines had the form y = mx + b where m was the slope and b was the y-intercept. In statistics lines are described using the equation y = a + bx. Thus b is the slope! And a is the y-intercept! You would not need to know this but your calculator will likely use b for the slope and a for the y-intercept. The exception is some TI calculators that use SLP and INT for slope and intercept respectively.

Note only for those in physical science courses. In some physical systems the data point (0,0) is the most accurately known measurement in a system. In this situation the physicist may choose to force the linear regression through the origin at (0,0). This forces the line to have an intercept of zero. There is another function in spreadsheets which can force the intercept to be zero, the LINear ESTimator function. The following functions use time versus distance, common x and y values in physical science.

=LINEST(distance (y) values,time (x) values,0)

Note that the same as the slope and intercept functions, the y-values are entered first, the x-values are entered second.

A probability is the likelihood of an event or outcome. Probabilities are specified mathematically by a number between 0 and 1 including 0 or 1.

We use the notation P(eventLabel) = probability to report a probability.

There are three ways to assign probabilities.

Intuition/subjective measure. An educated best guess. Using available information to make a best estimate of a probability. Could be anything from a wild guess to an educated and informed estimate by experts in the field.

Equally Likely Events: Probabilities from mathematical formulas

In the following the word "event" and the word "outcome" are taken to have the same meaning.

The study of problems with equally likely outcomes is termed the study of probabilities. This is the realm of the mathematics of probability. Using the mathematics of probability, the outcomes can be determined ahead of time. Mathematical formulas determine the probability of a particular outcome. All measures are population parameters. The mathematics of probability determines the probabilities for coin tosses, dice, cards, lotteries, bingo, and other games of chance.

This course focuses not on probability but rather on statistics. In statistics, measurement are made on a sample taken from the population and used to estimate the population's parameters. All possible outcomes are not usually known. is usually not known and might not be knowable. Relative frequencies will be used to estimate population parameters.

Where each and every event is equally likely, the probability of an event occurring can be determined from

probability = ways to get the desired event/total possible events

or

probability = ways to get the particular outcome/total possible outcomes

P(head on a penny) = one way to get a head/two sides = 1/2 = 0.5 or 50%

That probability, 0.5, is the probability of getting a heads or tails prior to the toss. Once the toss is done, the coin is either a head or a tail, 1 or 0, all or nothing. There is no 0.5 probability anymore.

Over any ten tosses there is no guarantee of five heads and five tails: probability does not work like that. Over any small sample the ratios of expected outcomes can differ from the mathematically calculated ratios.

Over thousands of tosses, however, the ratio of outcomes such as the number of heads to the number of tails, will approach the mathematically predicted amount. We refer to this as the law of large numbers.

In effect, a few tosses is a sample from a population that consists, theoretically, of an infinite number of tosses. Thus we can speak about a population mean μ for an infinite number of tosses. That population mean μ is the mathematically predicted probability.

Population mean μ = (number of ways to get a desired outcome)/(total possible outcomes)

A six-sided die. Six sides. Each side equally likely to appear. Six total possible outcomes. Only one way to roll a one: the side with a single pip must face up. 1 way to get a one/6 possible outcomes = 0.1667 or 17%

P(1) = 0.17

The formula remains the same: the number of possible ways to get a particular roll divided by the number of possible outcomes (that is, the number of sides!).

Think about this: what would a three sided die look like? How about a two-sided die? What about a one sided die? What shape would that be? Is there such a thing?

Ways to get a five on two dice: 1 + 4 = 5, 2 + 3 = 5, 3 + 2 = 5, 4 + 1 = 5 (each die is unique). Four ways to get/36 total possibilities = 4/36 = 0.11 or 11%

Homework:

The sample space set of all possible outcomes in an experiment or system.

Bear in mind that the following is an oversimplification of the complex biogenetics of achromatopsia for the sake of a statistics example. Achromatopsia is controlled by a pair of genes, one from the mother and one from the father. A child is born an achromat when the child inherits a recessive gene from both the mother and father.

A is the dominant gene

a is the recessive gene

A person with the combination AA is "double dominant" and has

"normal" vision.

A person with the combination Aa is termed a carrier and has "normal" vision.

A person with the combination aa has achromatopsia.

Suppose two carriers, Aa, marry and have children. The sample space for this situation is as follows:

| mother | |||

| father | \ | A | a |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | AA | Aa | |

| a | Aa | aa | |

The above diagram of all four possible outcomes represents the sample space for this exercise. Note that for each and every child there is only one possible outcome. The outcomes are said to be mutually exclusive and independent. Each outcome is as likely as any other individual outcome. All possible outcomes can be calculated. the sample space is completely known. Therefore the above involves probability and not statistics.

The probability of these two parents bearing a child with achromatopsia is:

P(achromat) = one way for the child to inherit aa/four possible combinations = 1/4 = 0.25 or 25%

This does NOT mean one in every four children will necessarily be an achromat. Suppose they have eight children. While it could turn out that exactly two children (25%) would have achromatopsia, other likely results are a single child with achromatopsia or three children with achromatopsia. Less likely, but possible, would be results of no achromat children or four achromat children. If we decide to work from actual results and build a frequency table, then we would be dealing with statistics.

The probability of bearing a carrier is:

P(carrier) = two ways for the child to inherit Aa/four possible combinations = 2/4 = 0.50

Note that while each outcome is equally likely, there are TWO ways to get a carrier, which results in a 50% probability of a child being a carrier.

At your desk: mate an achromat aa father and carrier mother Aa.

Homework: Mate a AA father and an achromat aa mother.

See: http://www.achromat.org/ for more information on achromatopsia.

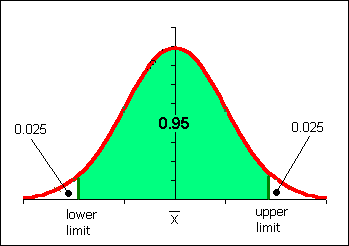

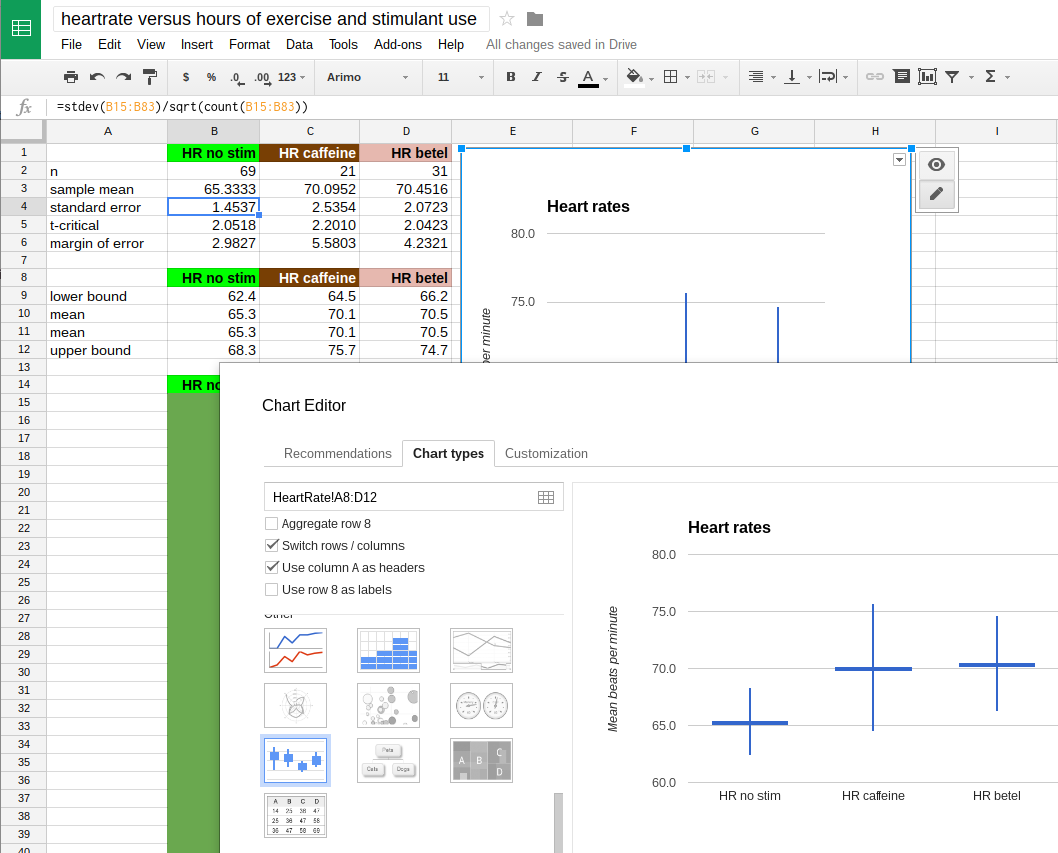

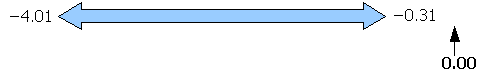

Genetically linked schizophrenia is another genetic example: