Orthographic note: The spellings are those provided by the students. The student presentations are done under the constructivist theory of education where knowledge is jointly built. The spellings and the spelling variants provide discussion points. There is no intent that these spellings are in any way to be construed as official spellings. At the same time, there is no effort in class to force a student to change their spelling system. Through this open and accepting approach, this author has learned that spelling systems can be idiosyncratic and local to a motu, clan, family, or individual. Bearing in mind the ethnographic underpinnings of the course, the spelling systems presented are taken at face value. To go up to the board and repeatedly "correct" the spellings provided would discourage students from attempting to share what they know for fear of being embarrassed. As seen in the images of the board below, the spellings herein conform to that provided by the students.

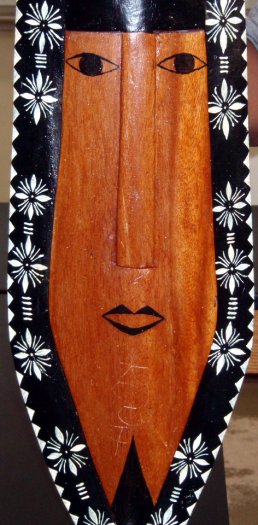

RS gave a presentation on the tepwanu masks of Chuuk. These masks are not worn, but rather are put on posts around a home or village. The masks protect the home or village. Translating the nature of the threat is not fully possible, the closest translations might be "evil spirits" or "malevolent ghosts." These masks work beyond Chuuk. Students from Chuuk had become concerned about ghosts in the library at night. A donation of a tepwanu was arranged and the mask was put on display in the library. The library is now traditionally protected.

Wilson brought in a pisinyela coconut cup.

Pernes displayed the ubiquitous Pohnpeian kiam.

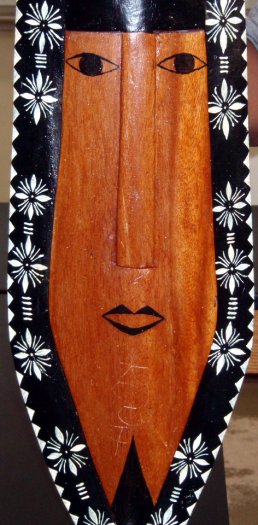

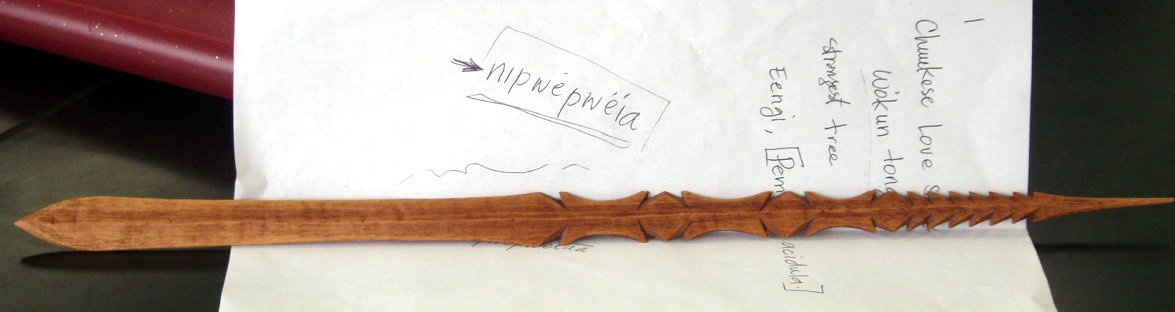

Greda from Faichuuk, presented the Chuukese love stick, the nipwepweiaa. No longer in use, in days of yore young men would make their own love stick and openly display the stick by day so women could come to know his love stick pattern. That night, he would stick the nipwepweiaa through the wall of her thatch hut and snag her hair. She could feel the stick and know what boy was on the other end. If she wanted to meet that boy, she could pull on the stick to let the boy know he can come in. Otherwise she pushed the stick back through the wall to indicate that she was not interested.

With the advent of cement walled homes, this world has been completely lost and now the nipwepweiaa is a trinket sold only to tourists. This is but a small part of what is a huge sea change in dating and mate finding practices in Micronesia. Young people who can afford cell phones now text message each other to set up a secret rendevous.

In the fall of 2005 Jayvina also presented the Chuukese love stick. Jayvina referred to the stick as a fenai and noted that open display did not occur. This may be a dialectical and regional practice differences in the lagoon. Jayvina also noted that the girl would slip out, rather than the boy coming in. This makes more sense given the mortal danger of being caught in the girl's home.

Note the spelling variation on the paper from that presented on the board. The stick is made from the Pemphis acidula tree (Eengi), a wood known for its strength. The need for strength and the shape suggests that in a pinch the love stick could be used defensively if a paramour was caught by angry brothers.

Aireen Lebehn presented a Mwoakillese traditional skirt called a dor. Discussion in the class included whether anything was worn under the dor in traditional times. Whether there was an underskirt for the dor was not known to Aireen.

The dor is made from pandanus leaves and coconut fiber.

The Yapese ong is made from four plants. Cassandra brought in this ong.

The lower skirt (bangan) consists of colored, dried hibiscus inner bark and dried banana leaves. The banana leaves are carefully "shredded" and dried.

The upper skirt (tarchaen)also includes uncolored leaves of the ti plant, Cordyline fruticosa. This upper skirt accentuates the hips and increases the hip to waist ratio. Some theories suggest that this is designed to appeal to subconscious mate selection behaviors. In these theories a small waist and wide hips signal that a woman is fertile and capable of bearing children, and not presently pregnant.

Coconut cord fiber is used to bind the top of the skirt.

A local plate called a pwaht in Pohnpeian was presented by Emyleen.

Emmy displayed the Yapese local betelnut bag called a fnowul.

Sheila brought in a belt that uses coconut fiber and shells. This belt is used to keep a Yapese skirt on.

Stephen Iphraim from Noumeneas presented the chük. Raw food is placed into the basket while the basket is being woven and then the weaving is completed sealing the food inside. Typically used to carry food to a feast.

Zachary displays the larger shenn and the smaller rhiugiun pwen baskets. The larger holds food and has side weaving that puts the finishing knots at basket bottom. The smaller rhiugiun pwen is used for carrying anything, often for carrying betel nut. One cannot enter a village empty handed, carrying the rhiugiun pwen is sufficient and common.

The knots on the rhiugiun pwen are slightly higher up the side of the smaller basket.

Kosraen dresses then...

... and now

Kosrae's pre-contact clothing culture was lost in the mid to late 1800s. As a result, their material clothing culture is that engendered by the church. Yet clothing is not static. The shift to sewn cotton fabrics opened up evolution of style. Bev and Evelyn model the clothes of yesterday and today. Bev models a mumu in typical use thirty years ago. Evelyn sports a more modern dress.

The koahr was used to weave thatch roofing. The wood needle had to be sharp, and was poked through the thatch and then used to pull the weaving cord back through the thatch like a crochet needle. Today the koahr has been all but replaced by the use of a nail to weave the thatch, the nail acting like a large needle.

In Kosrae traditional soup was traditionally served with a mew yucyuc. In Kosraen the c is a silent marker of a short vowel. Kosraen and Pohnpeian were both designed to be keyboard friendly, using unused letters to signal long and short vowels. Some languages, such as those of Chuuk lagoon, remain written with diacritical marks.

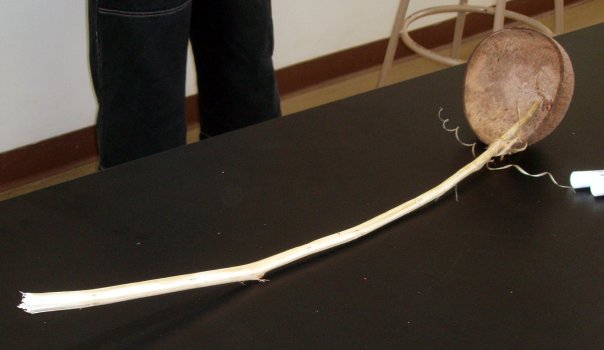

The ngarangar is used these days primarily in association with drinking sakau. Consumption of other liquids has moved to glasses. When used in a nahs with high titles present and sakau in the ngarangar, the ngarangar takes on a new name: kohwa. Priana presented the ngarangar. Discussion noted that the ngarangar is often handed down through the generations - they can last many years and are accorded great respect.

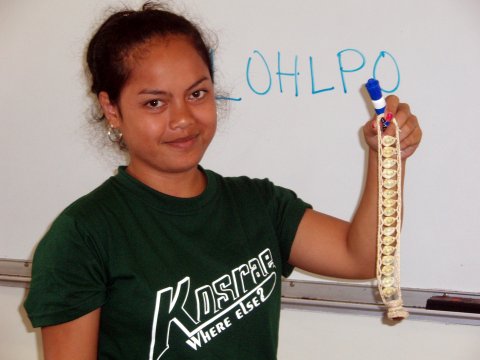

Michelle of Kosrae sports a bracelet called a lohlpo

On March 15th of each year the Kapinga people celebrate the completion of their taro patch. A few days prior to the 15th the men set eel traps out on the reef. The actual traps are the size of a small lab table. Then the traps are gathered and brought in for the feast. Teine noted that this happens only once a year. The trap is a called a uu.

Sherly presented the Kosraen fohtoh, a general purpose basket. The basket is most often woven for funerals or church dedications, plastic basins and tubs having displaced its functionality in family parties and feasts. Still, the only way to bring taro, coconuts, and other foods to a funeral is in a fohtoh. The actual basket is considerably larger, Sherly made a small one for display in class.

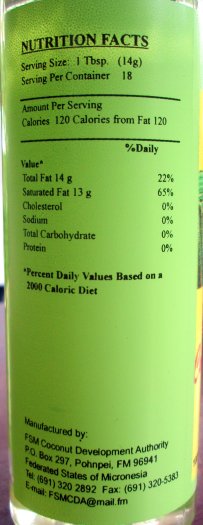

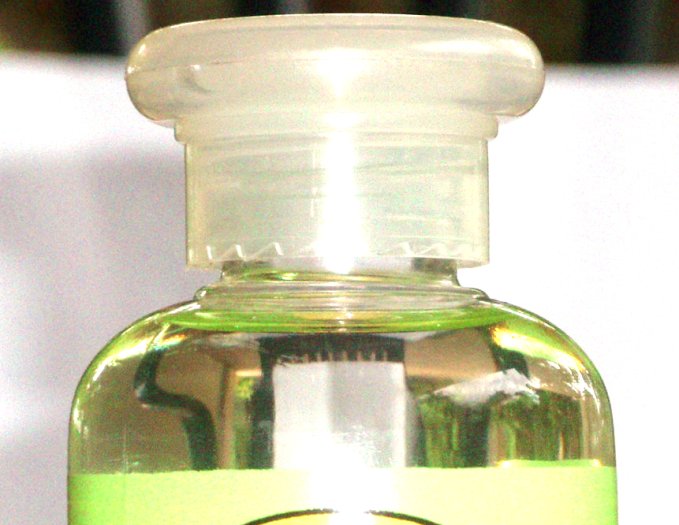

The oil has not been heated, the result being that the oil is clear and has no yellow coloration. The greenish tinging is due to the label. Note the white sheet of paper behind the bottle seen in reduction by refraction at the center of the image - the oil is clear.

Ethnoherb • Ethnobotany • Lee Ling • COMFSM